Most visitors would never guess this sleepy little island on the coast of Georgia gave birth to the most powerful financial system in modern history. Or that the genesis transpired in total secrecy. But that’s what happened, right here. How that came about in this remote place is an interesting tale, with an interesting backstory.

We have about 24 hours before heading north again, and a few errands to do first. This little marina turns out to have a couple of cars available to borrow; also some golf carts, and bikes. Doug realizes he can take a car to Brunswick on the mainland, and there maybe complete the Phone Case Quest, and definitely pick up some groceries. I opt to explore the island on bike in the meantime.

Very nice paved paths run along the river bluff the whole length of the island, and others shoot east out to the Atlantic. Conveniently, the paths pass the prime sights, from the shade of big live oaks.

All the Sea Islands along this coast, when first settled by the British, were parceled out as big plantations worked with slave labor. All of Jekyll Island was a single plantation owned by a fellow named Horton. He built the first brewery in Georgia, grew barley and indigo. He built a manor house of tabby, a regional form of sturdy concrete made with oyster shells. Near the north end of the island, I come to the remains of the house. The wood has weathered away, but the tabby walls remain – it’s one of only two two-story structures from the colonial era still standing in Georgia. It has a nice view of the sound across the marshes to the mainland.

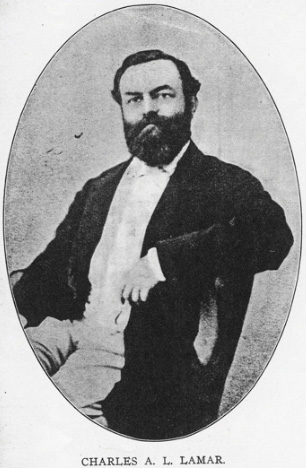

When Horton died, the island was acquired by a refugee from the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror, an aristocrat named Christophe du Bignon. The du Bignon family prospered for generations by importing more and more African slaves to do the labor. In fact, in 1858, two du Bignon brothers conspired with a broke planter in Savannah, named Charles Lamar, on a plan to bring another ship full of Africans kidnapped from Africa – half a century after the Atlantic Slave Trade was outlawed. Consequently, the expedition holds the dubious distinction as the penultimate slave ship to arrive on American shores, and it landed them here on Jekyll Island at the direction of du Bignon.

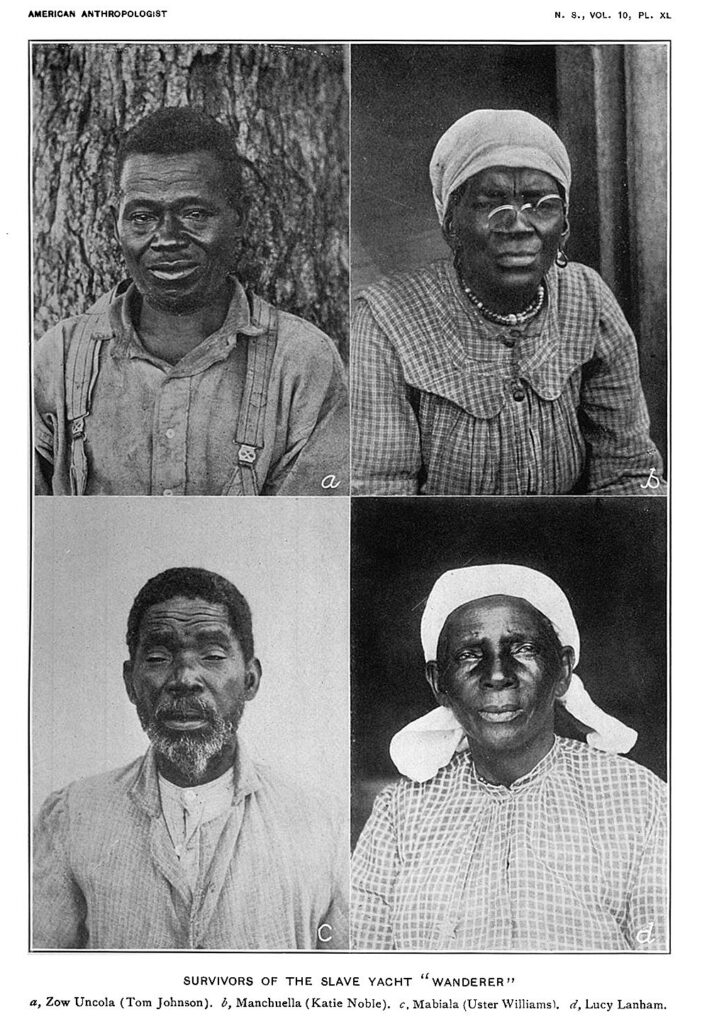

The full story is fascinating for all sorts of reasons, but here’s the short version. The ship, The Wanderer, was built as a racing schooner in New York. It was fast, achieving 20 knots under sail, and the largest racing yacht in the country. When purchased from the owner and brought south to Charleston, the plan to use it as a slave ship was already well known. But to avoid legal complications, it was only stripped of its luxury accoutrements in Charleston, then sailed to Africa where it was refitted to haul human cargo. Between 500 and 800 kidnapped Africans were bought and crammed on board. Exact numbers are unknown, but 487 were found listed in logs.

Only 409 survived the journey. Many were intentionally drowned in the Caribbean, weighted and thrown overboard when crew thought they were chased by patrols. The remaining people, those still alive, were landed on Jekyll Island. They were ferried over from the ship anchored off the beach, still flying the burgee of the New York Yacht Club, and smuggled to markets in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. This happened so late in our history that we have interviews and photo of some survivors from early in the 1900s. Their ancestors are still living in the Lowcountry keeping the Gullah-Geechee culture alive, some becoming important figures in contemporary history, even a Supreme Court Justice.

Despite the outrage the flagrant crime caused in the North, the people responsible were not convicted by a white jury in Savannah (rumor is the judge was father-in-law of the captain). So all involved went free. Except the Africans, of course.

Immediately, a second expedition was undertaken with the same ship and a new crew. To avoid liability for investors, the crew “stole it” for the mission. As the ship sailed away, it was theatrically pursued by the ship’s owner, “but he was like an Irishman looking for a day’s work, and praying that he might not find it” according to a report by a journalist. The crew, who were themselves kidnapped and pressed into service, mutinied off the coast of Africa, set the captain adrift in a rowboat, and sailed the ship back to Boston where it was confiscated. The whole episode created such outrage, North and South, the sparks helped ignite the tinder that started the Civil War. Shots were fired in Charleston just 18 months later.

Two bits of karma ensued. The Wanderer, now in possession of the Union, was used as a gunboat to blockade rebel ports throughout the war. And Colonel Lamar, the ringleader who initiated the scheme, was the last Confederate officer killed in the Civil War, just weeks before the war ended.

So du Bignon had already made quite a name for Jekyll Island in history books. Notoriety enough, but here is where things take a new turn.

After the Civil War, the business of running a plantation, without unlimited cheap labor, was decidedly less propitious. By the time the Union Army arrived, it was overgrown and abandoned, broken up among the remaining du Bignon family.

A decade later, one of those heirs, John Eugene du Bignon, bought up all the parcels from relatives and consolidated it again into one island property. He and a brother-in-law investor, one with northern connections, hatched a plan to turn the whole island into a private club for ultra wealthy Yankees. They transferred title to a corporation formed for the purpose, and sold membership shares to friends, enough to build the opulent Jekyll Island Club. This gave them a resort hotel “clubhouse” to market high dollar memberships in a deluxe “hunting and sportsman’s club” – limited to 100 to keep it exclusive.

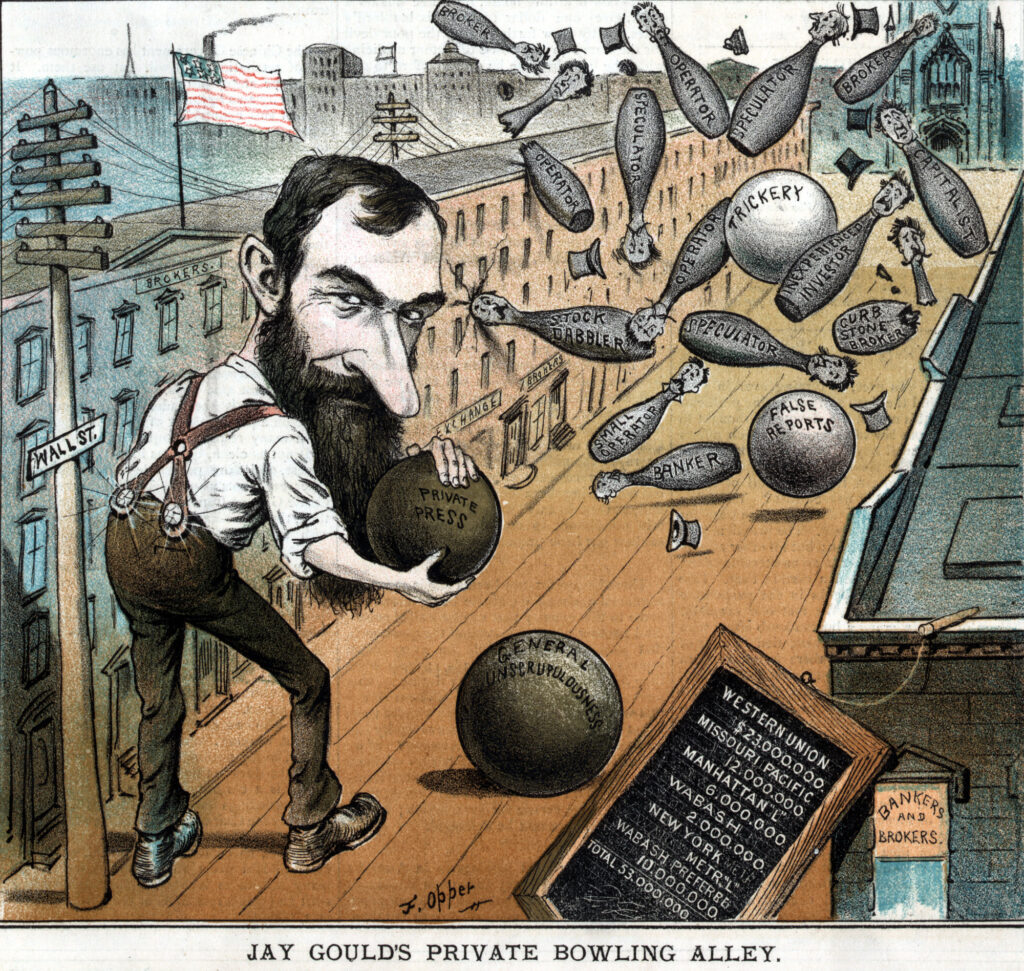

And it worked. From 1888 through the Gilded Age, it was a private playground for many of the wealthiest families in the world. The most gilded of the Gilded Age. The most affluent among them built their own “cottages” on the island – mansions in their own right – for their own private use. Members with names like J.P. Morgan, Marshall Field, Henry Hyde, Jay Gould, Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Pulitzer, Mellon, Goodyear, and so on. Businessmen in a club called by journalists “The Robber Barons”.

It was within this rarified enclave that the Federal Reserve System was created. Banks had always been independent affairs, operating as separate businesses. The lack of distributed risk and financial support resulted in frequent “bank runs” or panics. You may remember this is one of the main plot twists in the movie “It’s a Wonderful Life” – a bank run threatens to ruin George Bailey and his community Savings and Loan.

But there was also a deep and universal mistrust of powerful central banks (like the one run by greedy and dishonest Mr. Potter). This mistrust of manipulative monied cabals dates back to before the birth of the Republic. It was a big sticking point when drafting the Constitution. Attempts to form a more stable central bank backed by the Federal Government had always failed.

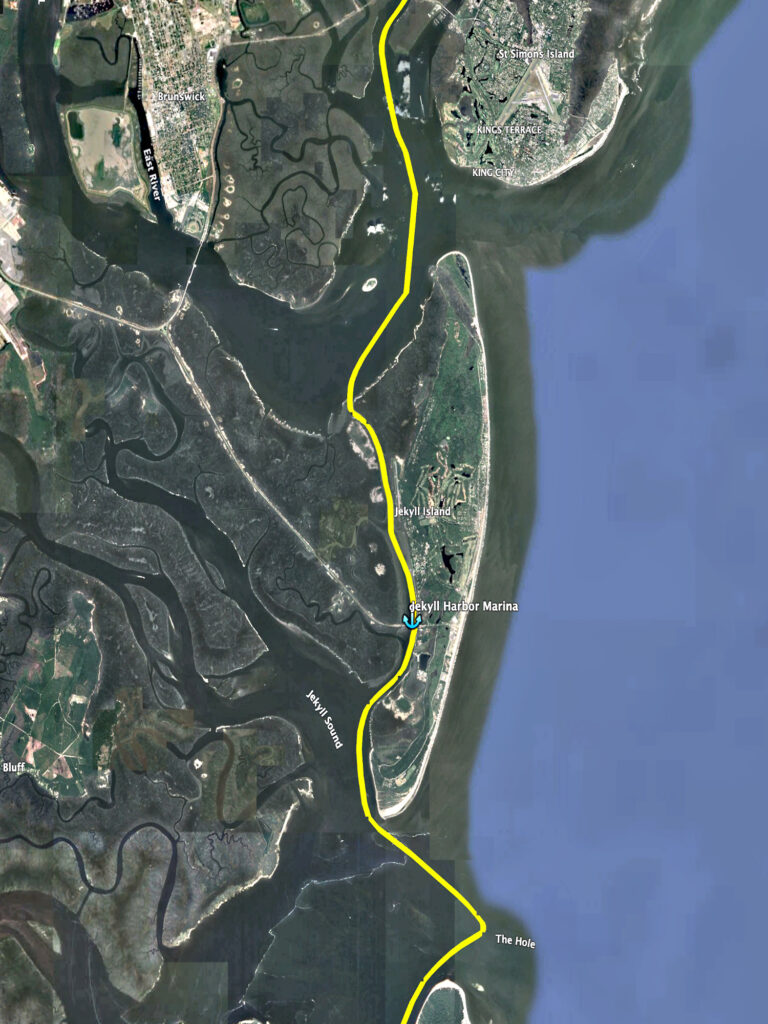

So, following the Panic of 1907, powerful New York and Chicago banking scions met to create a central bank and more stability, at the behest of the US Treasury Secretary, but they had to do it in secret. Members of the mission told friends and families they were going duck hunting. Because they had such famous names (see above), they were instructed to travel using aliases and tell no one what they were doing or where they were going. They boarded private rail cars at small secluded sidings, and rode all night to the little town of Brunswick, Georgia, known mostly for making turpentine. There they took boats over to a semi-tropical private island, one with a nefarious connection to the slave trade and economic system that built their vast fortunes – first by financing the industries of slavery, then by financing the war against it, then by literally capitalizing the opportunities created in the aftermath.

Sequestered away for weeks with representatives of the US Treasury, they spent all day every day at the Club hammering out a plan for a centralized Federal banking system that would underwrite them all.

Together, they represented one quarter of the wealth of the world at that time. If word got out that this cartel of bankers were plotting together in secret, a universal uproar would have sunk the whole thing. For the duration, they used only their code names so even the staff serving them would not know who they were or what they were up to.

But they managed to pull it off. Three years later, Woodrow Wilson signed legislation that created the Federal Reserve System, and the US has had a central bank ever since. It is not known if these bankers took any ducks home.

In 1915, the first transcontinental phone call was made from the club by the president of AT&T to Alexander Graham Bell and President Woodrow Wilson. The club had its own taxidermist to artfully produce trophies of animals bagged in managed hunts, and wild game was often on the menu prepared by the best chefs. Golf courses, tennis courts, croquet, carriage rides – whatever popular recreation the members wanted was provided.

But hard times came again for the Jekyll Island Club during the Great Depression. Though wealthy elites were not as inconvenienced as dimmer stars of lesser constellations, membership in an expensive club so far from home was easily expendable. Membership shrank while operating costs remained high.

By World War II the Club was insolvent and had to close. The Army moved in. Soldiers bivouacked in the same dining room and ate canned rations where the fabulously wealthy had champagne and caviar served on silver and crystal. Lookouts scanned the Atlantic for German U-boats from towers on same beach that was the exclusive bathing venue for ladies of high society.

After the war, the island and its facilities were decayed and neglected. Developers, sensing a rare opportunity, began circling the corpse with the idea of splitting it up into prime housing sites. It was destined to become another private beachfront development like Hilton Head, where only those who own property would have access.

The state of Georgia came to the rescue, after a fashion, and condemned the whole island in order to preserve it for the public as a state park. However, governments are not known for expertise managing resort properties, and the project failed quickly. Finally, it was declared a historic landmark to offer some protection. Then management was turned over to a for-profit hotel corporation. Work began restoring some of the former glory, while keeping areas like campgrounds and beaches open to the public. On the Atlantic side is now a convention center, some new hotels and condos, and a neighborhood with homes built in the 1960s and 70s.

The original Clubhouse and most of the mansions are still here, and well maintained. I ride among “The Cottages”, some of which are now gift shops and museums, some for rent. Then around the Jekyll Island Clubhouse, which now operates successfully as a high-end resort. At least a dozen weddings are underway on wide manicured lawns under big white tents. More spill out of cottages into their gardens like flocks of pastel chickens around fancy coops.

Later that night, I make the same circuit again. It’s lovely in the moonlight. Strings of Japanese paper lanterns sway in the sea breeze. The receptions are over, a few tipsy guests wobble about on shoes not meant for walking in grass.

I dodge crews in motorized carts collecting chairs and pulling down tents, and stop on the bluff to watch a tug pushing a barge up the river. The spotlight slashes over the marsh like an electric saber. When it strikes beards of Spanish Moss they glow incandescent. The “Cajun Radar” from Doug’s stories of the Gulf.

Before turning in, I make one last loop around the Club, glowing like a cruise ship. Where elite bankers once reclined with Cuban cigars and cognac, plotting world domination, after-wedding parties are in full swing. Music and laughter flow out over the lawn, mixing with moonlight and katydids.

Another scene out of Gatsby.