YOUR QUEST IS COMPLETE. ADVANCE TO LEVEL 4.

We’ve had beautiful weather for 8 days and 150 miles, all the way from Daytona. That will change today.

Doug returned from Brunswick with a bounce in his step and a smile on his face. He finally found that rarest of treasures: a new phone case. He has bags with enough provisions to last several days. Anything seemed possible now! We stow the food, shove off, and head north. The gleaming tower of the Jekyll Island Club recedes over the trees like Cinderella’s castle, and I get to hear the story of his quest.

Turns out Brunswick is quite the busy little town now. When I was a kid, all I remember seeing of Brunswick was huge piles of ragged pine stumps – roots and all, mountains of them.

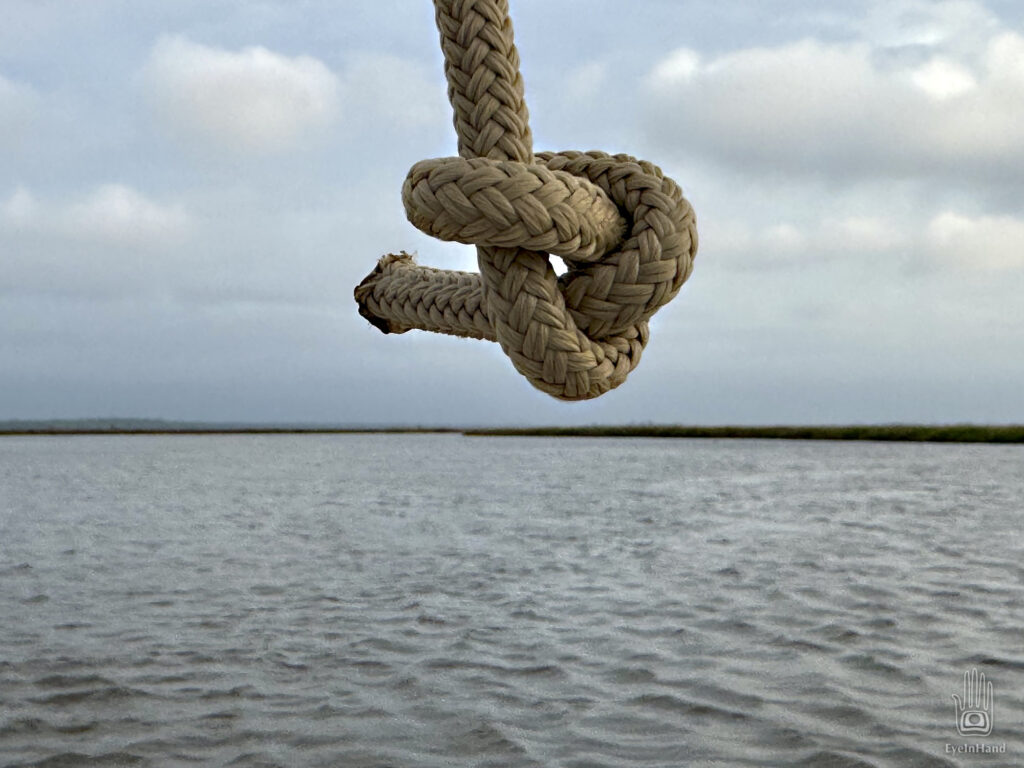

The vast Longleaf Pine forests of eastern North Carolina were once the source of virtually all critical Naval Stores for the British Royal Navy, beginning in the 1600s. “Naval Stores” is an oddly vague term. Beyond the prime timber for masts and planks, it refers specifically to all the maritime products derived from pine sap — including pitch, tar, rosin, and turpentine. It was used to waterproof and preserve wooden ships and much of their gear. It made hemp rope and rigging stronger and delayed decay; it saturated cotton cordage for caulking seams to make planking stiff and watertight; barrels of tar were mopped onto decks to fill cracks and stop leaks. When whale oil became scarce, turpentine was mixed with alcohol and used as lamp oil on ships and in cities until it was eventually replaced by kerosene.

The industry was so large that people of North Carolina were known as Tar Heels, from the sticky black sap that stuck to anyone working the pine woods. It’s where we get nautical terms like “Jack Tar” and “Old Tar” for sailors.

I always had sticky pine sap all over me as a kid. It smelled wonderful, but you couldn’t wash it off. Not soluble in water and impervious to soap, it wouldn’t come out of our clothes. Once sapped, you just had to throw them away. It drove my mother crazy. If it got in your hair, forget it — you just had to cut your hair off. We still have some terp tins from Georgia, incorporated into wall art.

When the North Carolina forests were finally stripped bare, crews moved south along the coast. The port of Brunswick became the new center of production, and large refineries were built there to do the processing and ship products to ports all over the world.

Sap is a pine tree’s self-defense system. When the scaly bark is breached, the tree tries to fill the wound with this incredibly sticky goo, sealing off the live wood from insects and fungus. Since rain won’t dissolve the stuff, it eventually hardens, serving as a barrier until the tree can regrow and fill the gap. Anything stuck in the goo is encased in what eventually becomes amber.

Harvesting sap involves “tapping” the tree by making a series of V-shaped cuts to encourage oozing. The ooze is caught in a drip tin, and new cuts are made as the old ones heal. The trick is to do this as much as possible without killing the tree. Once the tree gives up, it’s “tapped out,” and the tree is cut down for timber. After that, the whole stump – rich in resin – is ripped from the earth, crushed, and steamed to extract whatever value is left.

By the time I was a child in Georgia, there were no more pine forests along the coast. The only thing remaining was the stumps I saw piled outside Brunswick. The turpentine mills are still in operation. Now, apparently, there are also big-box stores, where Doug easily found his phone case.

We have good sailing up the Mackay River along St. Simons Island, another Sea Island almost as big as Cumberland. We wind through broad marshes all day.

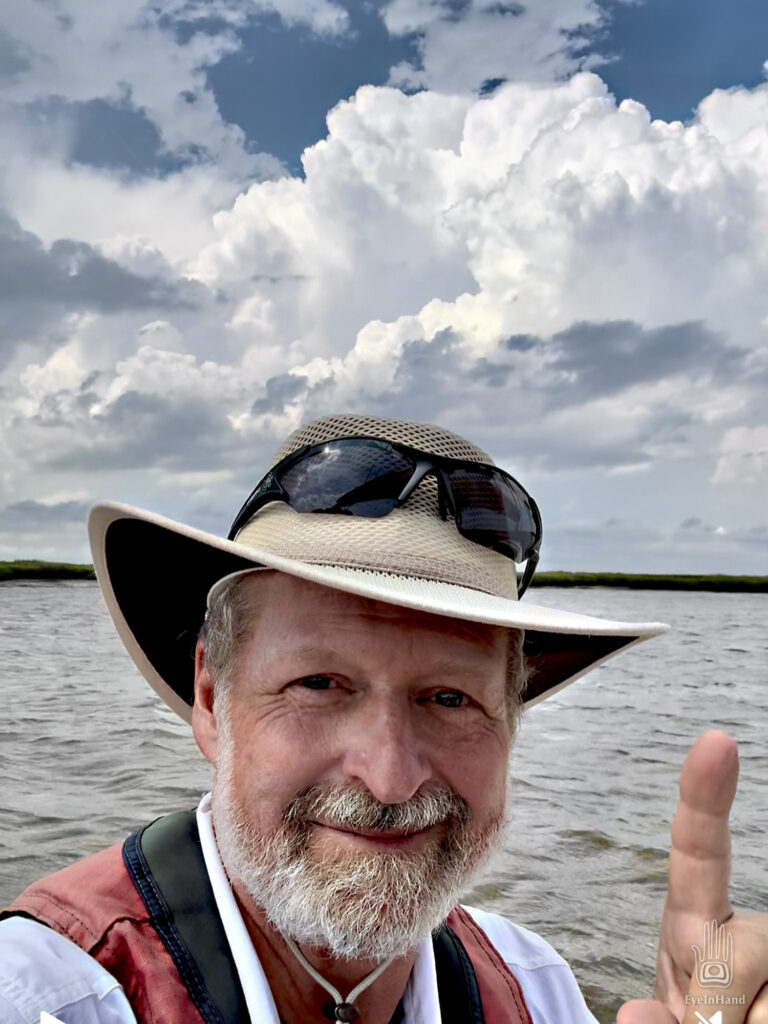

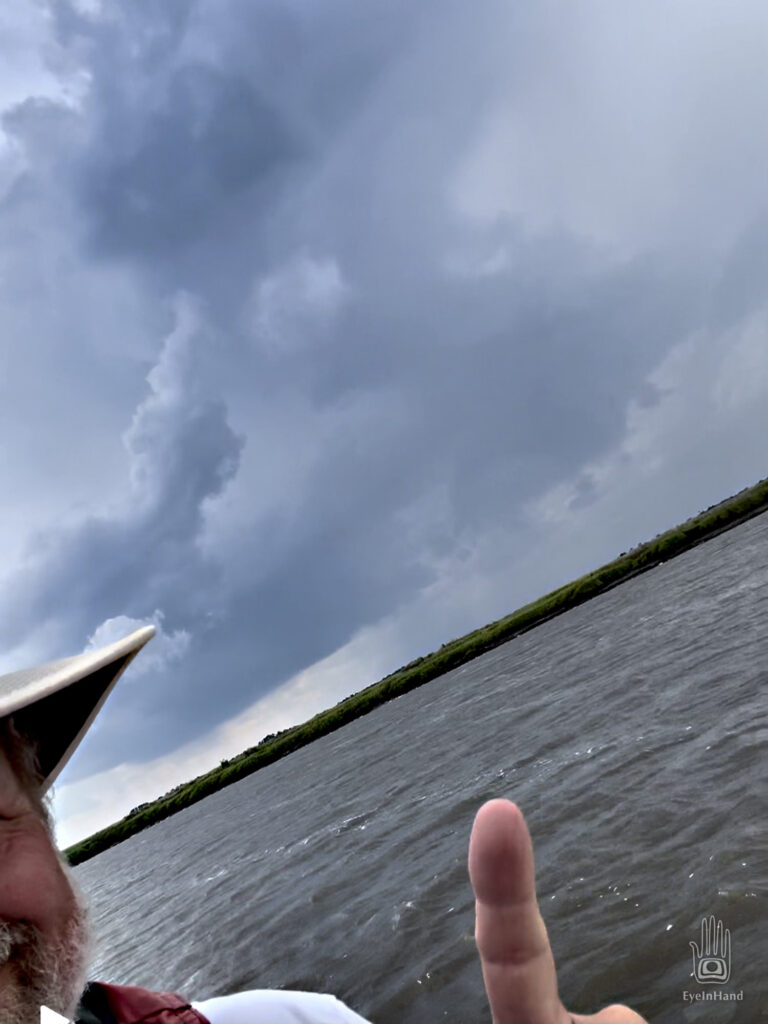

By late afternoon, the sky fills with ominous clouds that pile up high ahead. At first we think it’s just an early summer shower, but they continue to tower higher and higher to the west and north. We can see rain pouring out of some in broad gray curtains, with flashes of lightning. The formerly steady wind stutters, with short gusts from new directions.

So far we’ve been able to stay in a clear pocket, blue sky overhead, but we’re increasingly surrounded, and our happy little bubble is shrinking. We drop the sails and stow loose gear so we don’t get caught by surprise. Our destination is a small creek on the north end of St. Simons Island, still about 6 miles away. I predict, optimistically, that the storm will split around us, exhaust itself by the time we get there, and leave us with a pleasant evening. This turns out to be both mostly correct and way too optimistic.

It’s getting late in the day. Dim light soaks through the storm clouds, and the air is heavy. Everything looks bruised.

In the 18th century, this part of the coast was known as “The Debatable Land.” It was intentionally kept a no-man’s-land to be an empty buffer between British South Carolina and Spanish Florida. Fort Frederica is just east of us on a side channel. A tiny fort with a tiny village, settled by ne’er-do-wells flushed from debtor prisons and shipped over from England and Scotland — people considered expendable fodder on the front line against frequent Spanish incursions. It was the era of the War of Jenkins’ Ear, a decade-long conflict ignited when a British captain — also a smuggler — had his ear nicked during a Spanish Coast Guard inspection. Two thousand Spanish troops landed on St. Simons and fought on both sides of where we now sail, in the Battle of Bloody Marsh, Gully Hole Creek, etc.. Basically, Europeans fighting over who could steal from the natives first.

Apparently, some things around here are still very much debatable. The area is so remote that channel markers are poorly maintained, often damaged or missing. Some guesswork is required to stay the course. At a confluence of creeks, the ICW may follow the smallest of three or four possible routes, so it’s counterintuitive. We make a couple of wrong turns and quickly correct. We pass the mast of a wreck sticking out of the marsh, a piece of tattered sail flying like a flag of surrender. These wrecks are scattered all along the coast from Florida to Carolina. We’ve seen hundreds of them, like memorials to past hurricanes. Not encouraging.

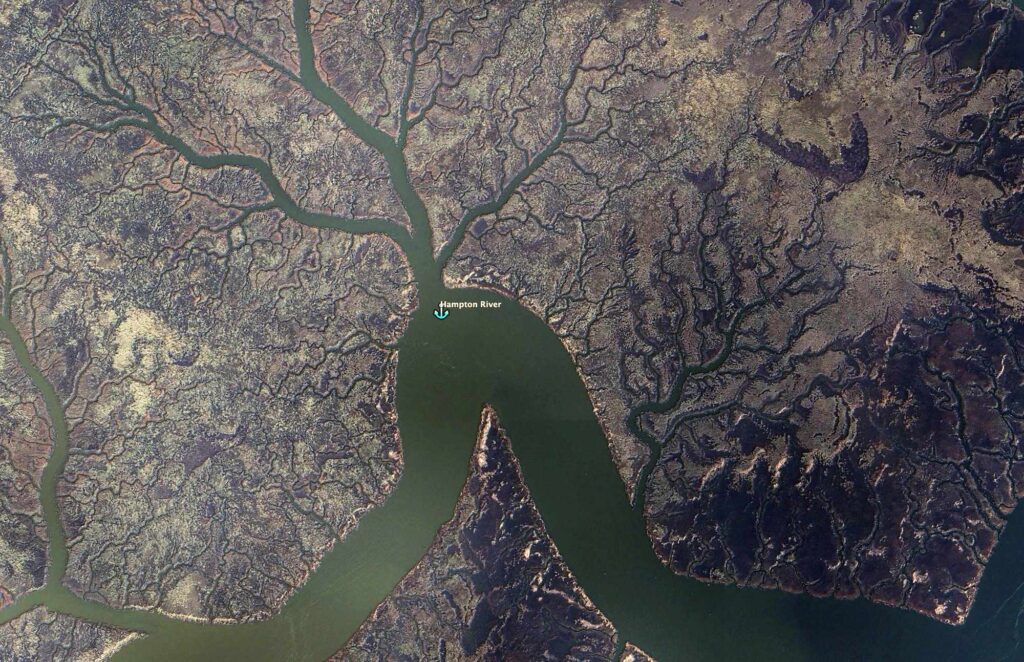

We’re looking for the entrance to Hampton Creek, a small tributary that nominally separates Little St. Simons Island from St. Simons Island. It’s very small. We would have missed it if not for a hand-painted sign blown over sideways – lackluster marketing for a distant marina. I just happen to spot it with binoculars looking back as we pass. We loop back and swing in.

Supposedly, this is a channel used by other boats with some regularity, but you’d never know it. The creek loops one way, then the other. We consider a couple of possible anchorages. In one side creek is another wrecked hull canted over in the mud. The shell of somebody’s lifelong dream. Again, not reassuring.

Ultimately, we end up as planned in a place Doug chose by studying maps months ago. It’s a good spot at a sharp bend in Hampton Creek. The water is deep, the creek narrow, so there’s not much fetch from any direction. We anchor out of the channel across from a day marker, tucked into a cozy nook surrounded by lush marsh grass.

It does indeed look like we dodged the worst of the storm. We can see it marching across the sky to the north. Before the sun sets, it peeks through and sends a shaft of light our way. In the distance, across the marsh grass, a small river tour boat navigates twists in the ICW, lights glowing on the upper deck. Birds are everywhere in the grass — red-winged blackbirds, cormorants, clapper rails. An alligator glides across the cove and disappears up the bank. Doug makes another fine dinner, and we can relax a bit before dark.

Late that night, we both bolt upright to an explosive bolt of lightning striking close, the flash and bang are instantaneous. A deafening roar of wind and rain. Before we can even get a light on, the boat heels sharply over, slammed by a powerful gust. We hold on as the boat swings around nose into the blast and rights herself. Rain comes down in torrents.

Lightning is flashing so fast through the tiny portholes I don’t need a flashlight to see. I find a radio and dial to a weather channel. We hear broadcast warnings, the mechanical voice drowned by waves of thunder, wind, and rain, so we have to listen several times through to get it all. Two waterspouts have touched down on Little St. Simons Island, moving east into the sound. Damage to watercraft and property. That explains the blast of wind. One must have passed just overhead.

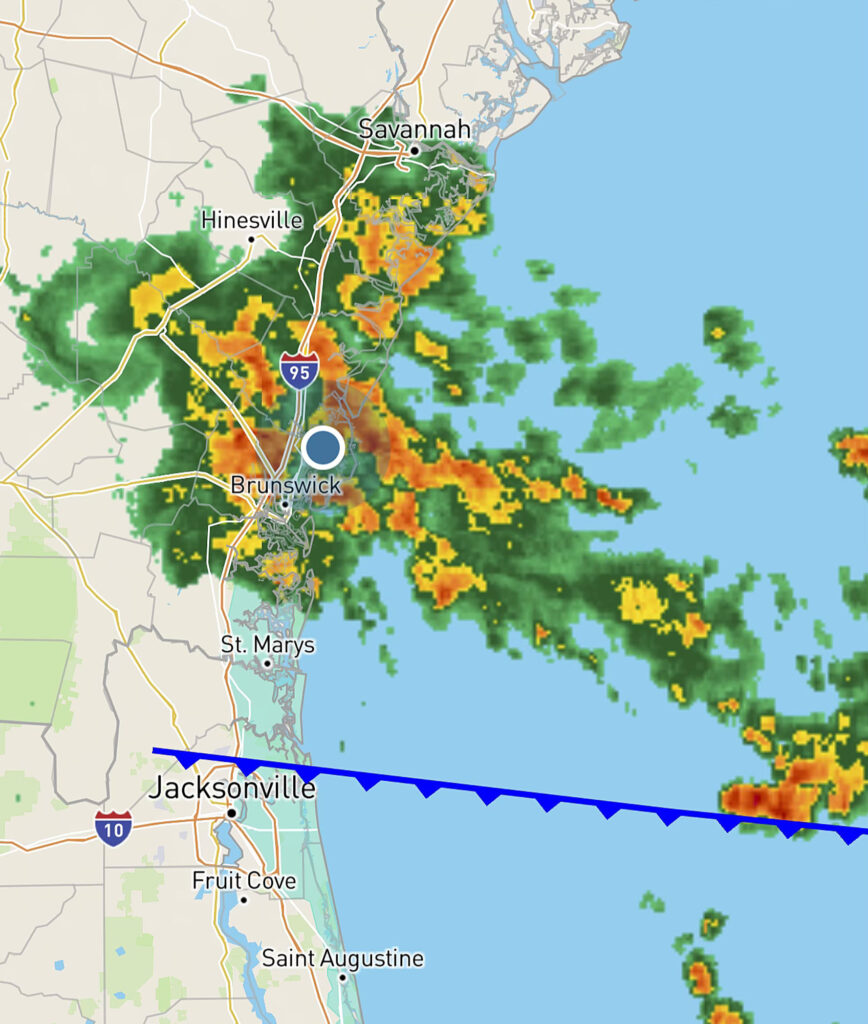

I pull up the radar on my phone. It’s a big storm spanning the whole 100 miles of the Georgia coast. And we’re right in the middle of it. But maybe the worst has passed over.

In the morning all is calm again. The dinghy is full of water, and so is the creek. The tide is so high it almost covers the day marker in the channel. We’re floating so high we can see over the flooded marshes for 360 degrees. Where yesterday was all grass is now all water. I bail out the dinghy while Doug gets the boat sorted out.

We haul up the anchor and head for that little marina of the blown over sign, further down the creek on St. Simons. Someplace we can get fuel, ice, and a full weather forecast.