Daufuskie Island Denied

It’s flat calm when we shove off from Skidaway Island. Back home in the Chesapeake, watermen called this a “Slick Ca’m” – a slick calm. The front has blown itself out. Beautiful weather is behind it, but the sails will stay furled all day.

We glide past the marine science center where I spent that summer digging in pluff mud, and enter a tangled patchwork of tidal rivers and marsh islands that scribble in the margins between ocean and land. We turn into Moon River, made famous in the song by Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer. I once had a toddler from the Creek tribe hold my hand at dusk and walk me to the bluff along this river. There he pointed excitedly at the sky to show me the object of the only word he knew – “Moon” – which he repeated over and over until he was sure I understood. We wondered at it together, a full moon rising through a curtain of Spanish Moss from a silver tray of salt marsh, until dark fell and the dinner bell rang.

Puffy clouds sail through the sky, mirrored in the water. A white columned plantation house is tucked back in the live oaks. A bald eagle stands sentry, pickets with a “no wake” sign.

A newish cruising catamaran falls into formation with us. No one is visible on deck or through tinted windows. Appears to be a bare boat charter or maybe a new captain, like he or she doesn’t know the rules of the road. They follow us around the buoys, through barges and cranes blocking bridges under construction. They don’t answer the radio, and don’t wave when we do. Just a silent scowling profile shadowing us for miles.

At Thunderbolt we make a short detour to loop through the harbor, one of the last working shipyards on this section of coast. It was once a busy commercial shipyard for fisheries and agriculture, but now serves the tony mega-yacht market. When I lived in Savannah, I waited on tables in a waterfront seafood restaurant here. LOTs of wild stories from that time. Like the night the whole staff – waiters, waitresses, chefs, busboys, dishwashers, even the manger – went skinny dipping in a hotel pool on Tybee Island after the all bars closed, until the police came and ran us off. The old restaurant is the only building still here along the waterfront from those days, but now it’s offices for the yacht basin.

Beyond Savannah we come to the Savannah River shipping channel. At this point we cross over the state line from Georgia to South Carolina. I had a friend who paddled this section in his kayak once. He met a container ship coming up the channel from the Atlantic. Realizing he could not get across fast enough, he pulled up along the bank to let it pass. The ship glided slowly by, a low grumble of engines like the ship had indigestion. My friend was ready to turn and cross when he saw the eight foot wake charging down the shore toward him. He braced as the waves lifted his boat high in the air and slammed it down on the rock revetment again and again until the wake finally dissipated. He had to climb up the bank and wait for a passing powerboat to take him back home, the kayak busted to pieces.

We see no ships today, though several we just missed are visible coming and going on AIS. In short order we enter a new state.

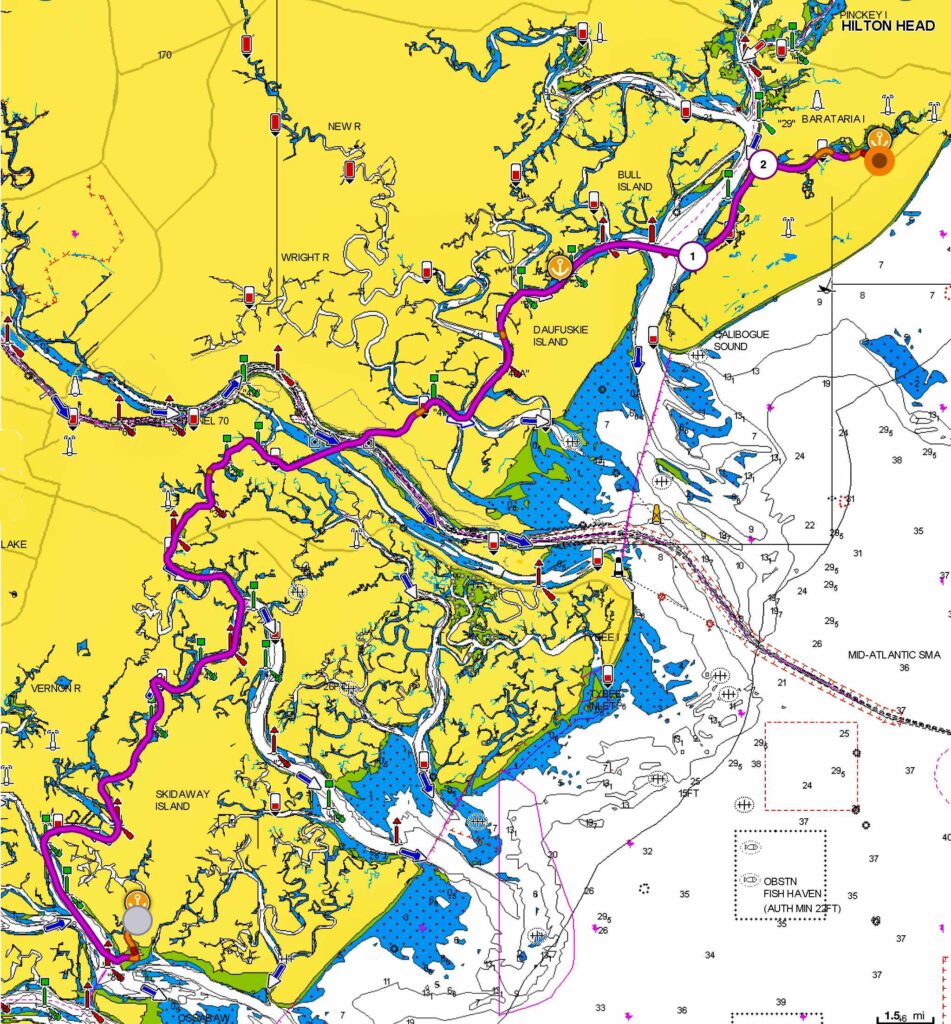

The remote southern tip of South Carolina is still empty and wild. Not much here. Our plan is to stop at a tiny marina on Daufuskie Island, the first inhabited island you come to as you head north from Savannah. Though linguists will debate the origin of the name, the story among locals is the name “Daufuskie” derives from the Taino language brought over with slaves in the 1500s by the Spanish, which lived on in the Gullah-Geechee dialect. To the English, it sounded like “dah-fust-key” as in “the first key” – from the Taino word cay for island.

Europeans built plantations before the Revolutionary War and then abandoned them during the Civil War. For centuries the only people who lived on Daufuskie were descendants of the Taino and escaped African slaves. It remained so isolated that the Gullah culture was preserved intact well into the 20th century. When the writer Pat Conroy was hired as a teacher there in the late 60s, the children did not know Kennedy was no longer president.

Though some development has encroached, it’s still a place where modern civilization only has a tentative hold. As we cruise the western shore, Doug can’t raise the marina by phone or radio. Passing our way mark we see why. It appears to have been closed for several years, though still shows up on maps and a web site with contact info. Most of the docks have collapsed. “Well, that explains why they didn’t reply to my email,” says Doug.

Now we have some decisions to make. There aren’t many affordable public facilities on this part of the coast. There aren’t many of any kind.

I try calling my brother for advice. He has lived in this area for years, worked in real estate and owned a boat. He knows of a marina on Hilton Head the locals use, called Shelter Cove. He hasn’t been there himself, just word of mouth. It’s 10 miles further north, but we can get there in a couple more hours. Doug gives them a call and someone answers. A promising start! The directions they give are a little . . . odd, however. It will make the longest day of the trip at 46 miles, and too late to change plans by the time we get there. With no better options at hand, we need to give it a try.

We cross Calibogue Sound on a strong outgoing tide and enter a creek that snakes into Hilton Head from the southwest. At first there are nice homes and docks along the shore, most with very nice boats hoisted up on lifts. Gradually those peter out and we pass through a sunken armada of abandoned boats. Some of them were once nice yachts. Some are derelict but still afloat, and seem to have permanent residents on board – shanties festooned with tarps and improvised shelters added on. The creek continues to narrow, even more with the tide now low, so we watch the depth finder and keep going.

Eventually we get to a small gap in the bank that otherwise matches the description Doug got over the phone. Can this be right? The way they described it, and given the high slip number we were given, it sounded huge. But this entrance is just a little S curve in the mud. I could touch muck to starboard and port with the boat hook. We wiggle through, pass a high retaining wall, and it’s like we’ve gone through the gates of Oz.