For those not interested in the details, here’s the video:

For years we used a Subaru Forester as a utility and travel vehicle. We could throw kayaks on top and bikes on the back, or haul a boat or utility trailer. Apparently, adding in coolers and camping gear, and us, far exceeded the load capacity it was designed for. This spring we broke both rear springs and struts. I got a finger wagging from my mechanic.

So we traded in the Subaru for a used truck that could handle the loads – a Honda Ridgeline that we’re really happy with.

The bed is too short for 17 foot boats, though. It came with a soft tonneau cover, but no roof rack. I could use the 3 ton utility trailer; but many of the local river launches aren’t big enough for that. And hooking up the utility trailer means no boat trailer, or bike rack. We need something more compact.

I looked at off the shelf ladder racks. These are heavy duty steel structures geared toward construction work, meant to stay permanently installed, which means wind noise and a hit on gas mileage all the time, whether you use them or not. It would also mean removing the bed cover. What we need is something lightweight for the kayaks and occasional long lumber, that’s quick to install and remove, so is only on the truck when needed.

The obvious quick and cheap solution is a homemade rack made of 2x4s that just sits in the bed. You can find examples of these online, many are well done. I don’t have a garage to store it in, though, so after sitting out in the weather I’d have to rebuild one every year, or disassemble it for storage. Pressure treated lumber would help with rot, but is heavy. All little annoyances that add up to too much hassle to just go for a short paddle or to fetch something from the lumber yard.

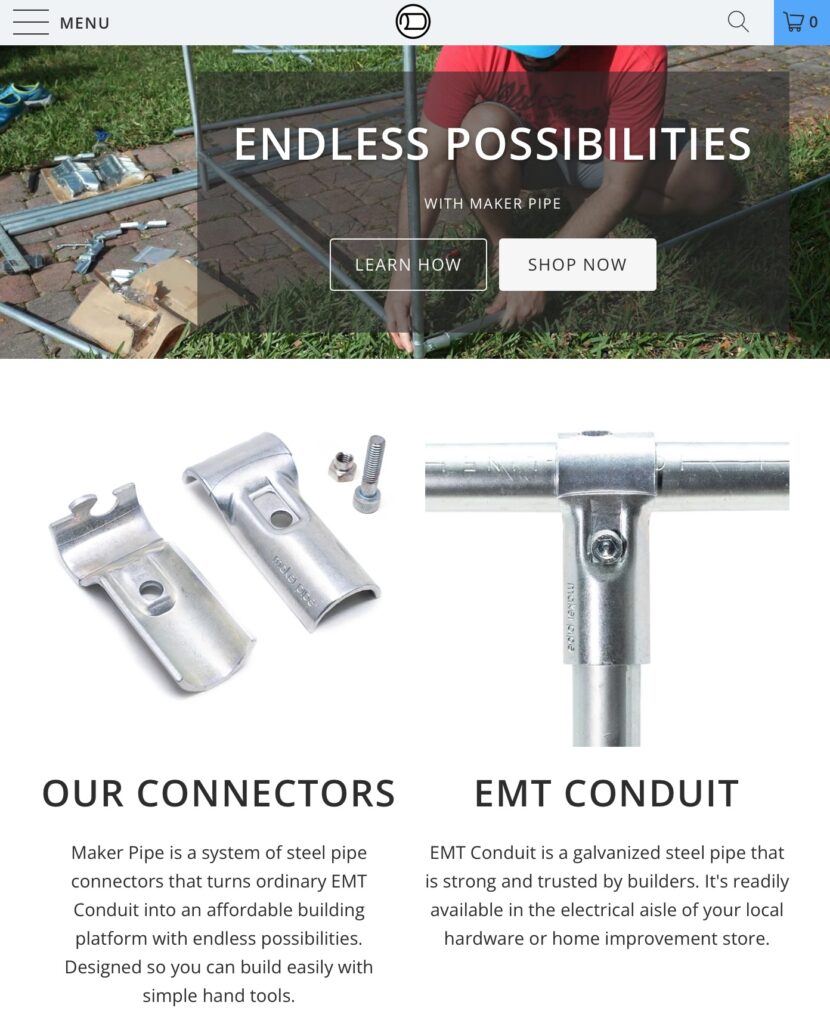

Searching deeper for ideas, I found a small company called Maker Pipe. I came across them years ago when they were running a successful Kickstarter campaign. They manufacture connectors to build all sorts of things out of EMT Conduit. Seemed like a cool idea at the time, but I had no idea they had spun up into a permanent business. Good for them! They’ve taken the idea further. They now make a variety of connectors for different needs, and their website and Youtube channel are chock full of useful fun ideas and helpful info, all geared to small projects like this.

EMT Conduit is galvanized pipe used for running electrical wire, especially in commercial construction. It’s mass produced in 10 foot lengths, which keeps the price low, and is readily available at any hardware or big box store. It’s rigid and strong, bendable, cuts with a simple pipe cutter, and because it’s galvanized inside and out, is rust proof. Maker Pipe’s connectors are also galvanized, so anything you build with these components can stay out in the weather. The whole idea was interesting enough to give it a try.

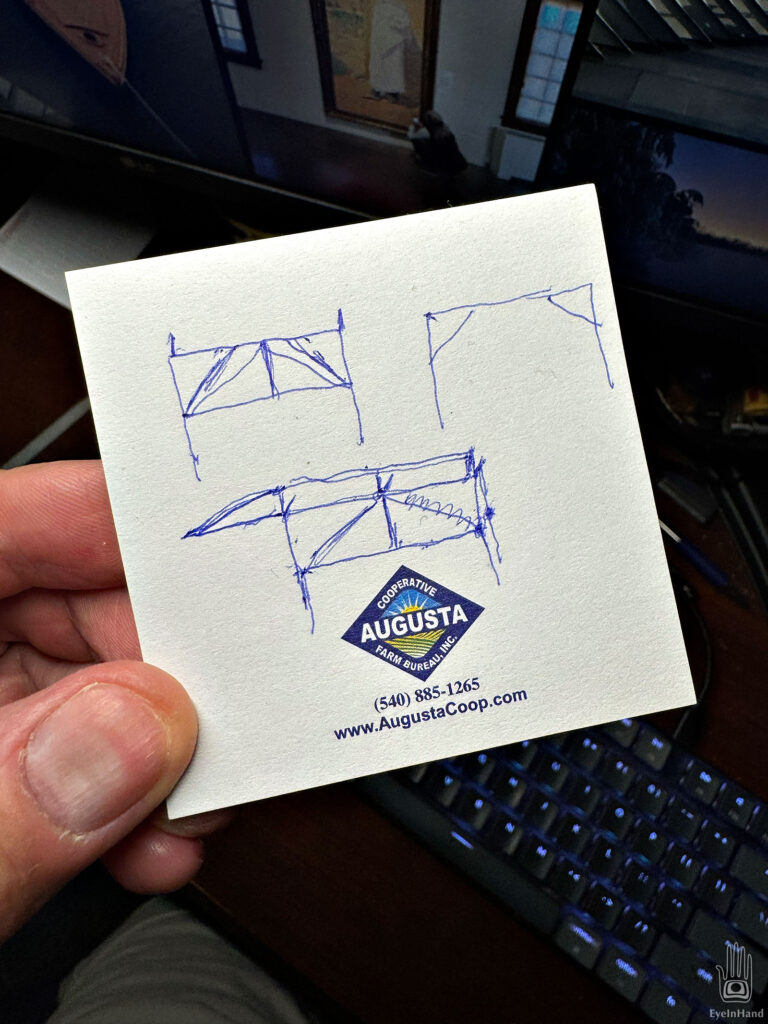

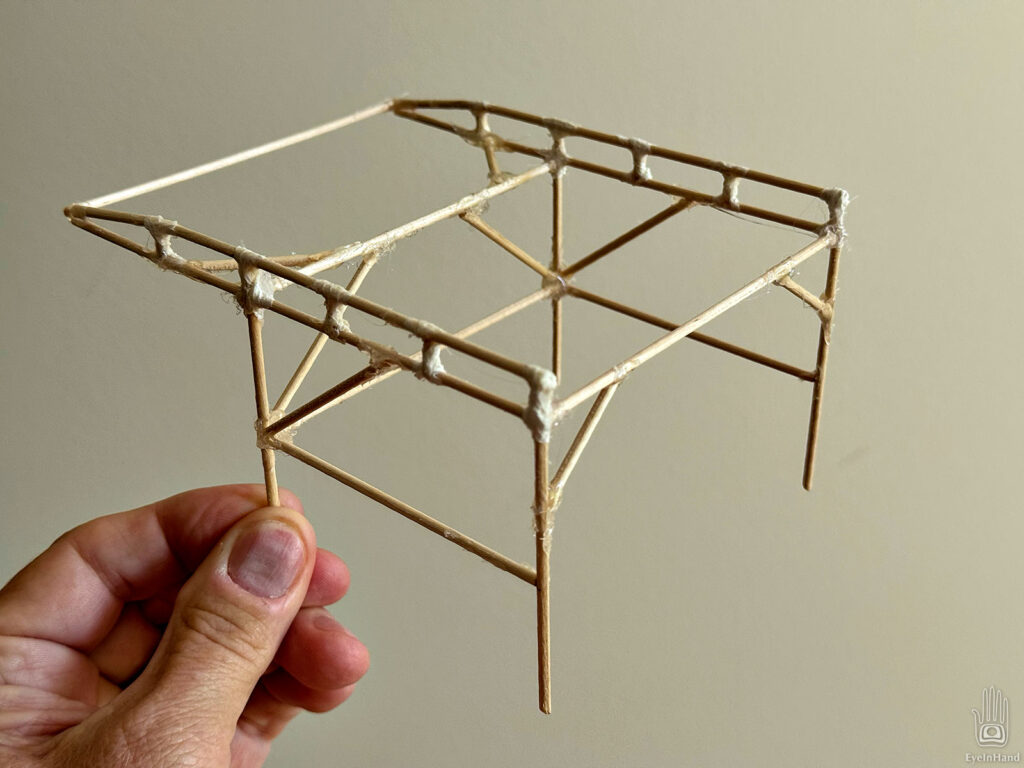

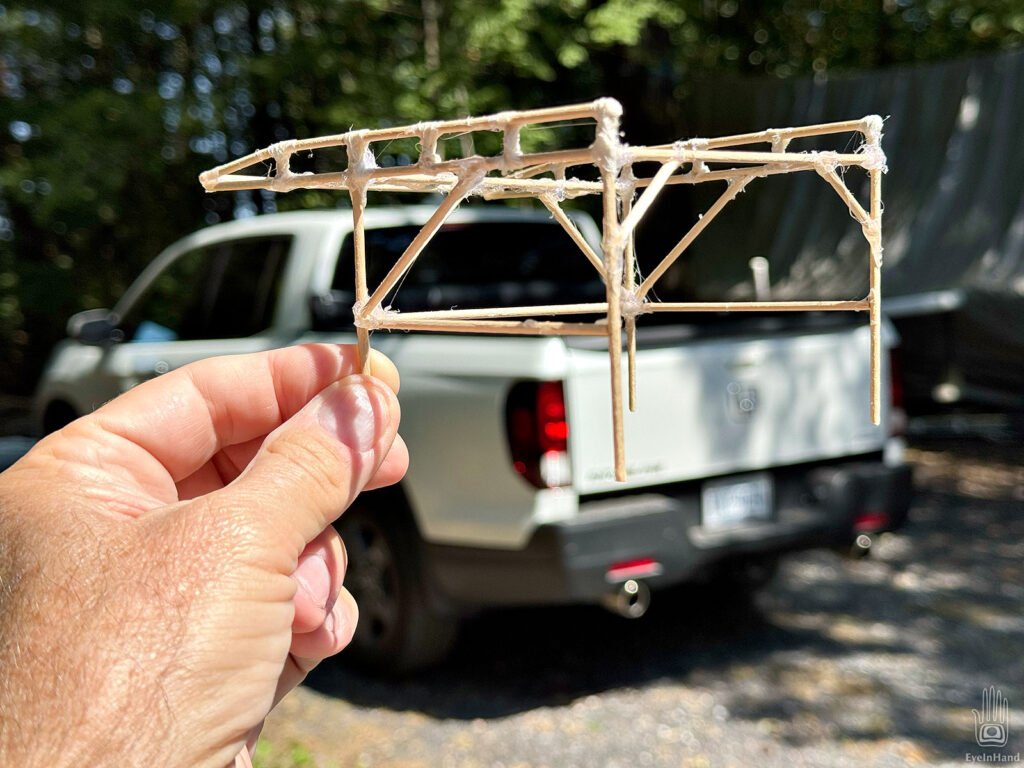

I started with a sketch, then made a model with sticks and hot glue to see how it would all come together.

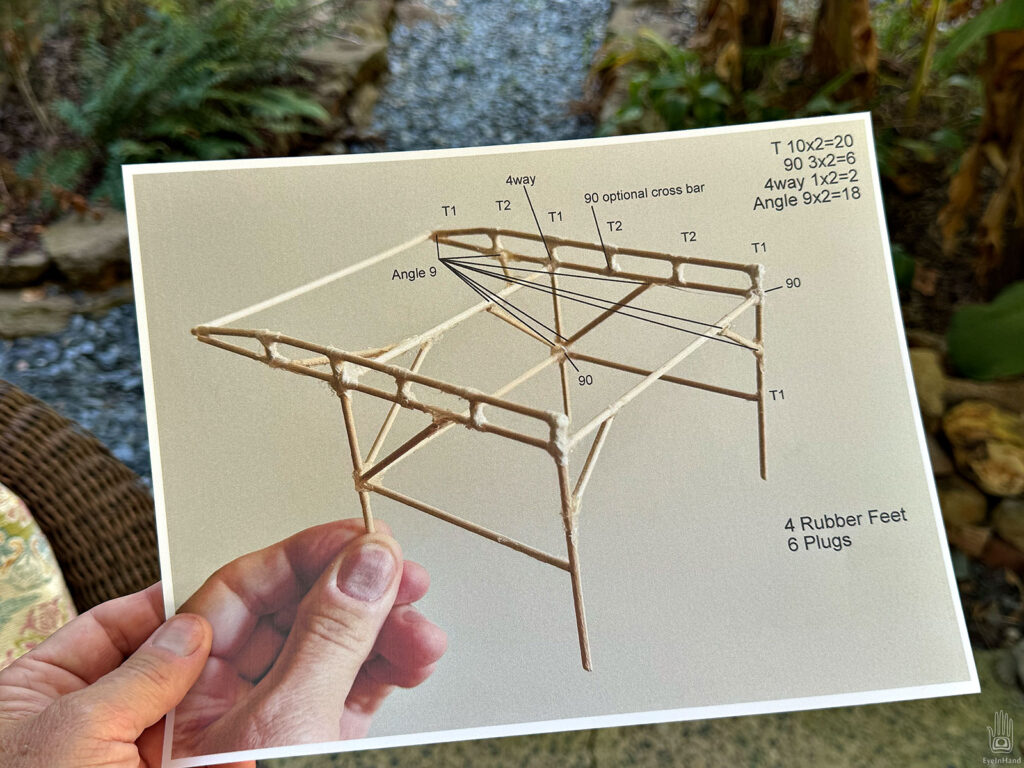

There were some things to sort out, like access to the trunk, leaving the rolled up cover in place, clearing the roof and shark fin antenna, etc. Then I printed a diagram to count up the various connectors and pipe needed.

Initially, I was going to use 1 inch conduit. Based on some fun non-scientific tests by the Maker Pipe team, it’s roughly twice as strong as ¾” pipe.

But 1″ pipe is also twice as heavy. Doing a little math I realized it would be pushing the limit of something I could lift and move around easily. Since I still have the utility trailer for heavy duty jobs, going lighter for this rack makes more sense.

The box of connectors arrived in a few days, everything nicely packed.

I did some mockups on the truck with clamps and pipe to get final measurements. Then the whole thing went together in couple of hours. Only tools needed were a pipe cutter and a 5mm hex key Allen wrench.

Next day I tested the fit and locked it in with turnbuckles to the existing tie down cleats in the truck, and went for a drive. There’s some wind noise at highway speeds, but not as bad as expected.

Final test was to throw a kayak on top and go for a paddle. Works great. Only takes about two minutes to lift it in and lock it down. And bonus, it fits nicely in the trailer.

With no further adjustment needed, I dabbed Loctite on all the nuts. Between temperature changes and vibration, don’t want anything jiggling apart at 70mph.

Overall I’m very happy with it. If it lasts 10 years I’ll be even happier.