The Chesapeake is known the world over as a popular sailing ground. The Naval Academy is in Annapolis with it’s top notch sailing program, and there are scores of sailing schools scattered all up and down the Bay. Marinas in every cove and creek are full of pleasure boats. As time approached for this trip, I began to wonder why I had heard so little of the great sailing to be had on Delaware Bay. It’s right next door, only 14 miles away – the same 14 miles the C&D Canal spans to connect them. They’re like sisters holding hands.

Studying its long shoreline on satellite images and charts, though, there are few signs of marinas to be found anywhere. I have friends living around Philadelphia and New Jersey who all sail. Except for a few local lakes, they almost always head for the Chesapeake for their adventures, or the sounds inside the barrier islands. Come to think of it, I don’t believe I’ve ever heard any of them talk about sailing on Delaware Bay, which is right in their backyard. What’s up with that?

When Paul and Jay mentioned Delaware Bay as we made our way north, it was with a mild sense of dread; obviously, they knew something I didn’t. Now I know: Delaware Bay is one nasty piece of water. If it’s the sister to the Chesapeake, it’s a wicked step sister.

Once we were in the Bay and heading southeast, Paul told me why. It’s just no fun at all. There’s a lot of commercial traffic moving in a very narrow channel. The rest of the bay is very shallow or fenced off by fish traps and duck blinds, so you have no choice but to stay close to the shipping lanes, making it very dangerous for small craft. You constantly have to stay alert to keep from getting run over or swamped by their wakes. Because it’s so shallow, and the current so strong, the water can get very rough very fast. You have to choose your weather window carefully.

Delaware Bay is one nasty piece of water. If it’s the sister to the Chesapeake, it’s a wicked step sister.

Even then, the Delaware is so large you can’t just sneak across – under the best of circumstances it will take 10 hours to go the distance, so you are guaranteed to have a strong tide against you at some point, and 10 hours is enough time for the weather to change dramatically from whatever it was when you started. All those things combined make it a stretch of water avoided when possible by people who know better. This was very interesting stuff to hear as darkness fell, and we began to make our way across said piece of water.

What makes these two large bays, otherwise so similar, so different?

Well, it starts with how they are oriented to the Atlantic Ocean. The Chesapeake has a relatively narrow mouth for its size, opening at a right angle to the Atlantic. This means ocean waves coming in can’t travel straight up the bay. A series of shoals protect the entrance, too – shallow enough to take some of the punch out ocean rollers, but deep enough they don’t impede traffic. Those two geographic features mean all that wave energy gets dissipated near the mouth.

The Delaware, on the other hand, opens its arms wide to the Atlantic, and with its long funnel shape, squeezes with an ever tightening embrace. The deep, wide channel at its mouth lets all that oceanic wave energy travel unimpeded all the way into the heart of the Bay. What happens next is what makes things really interesting.

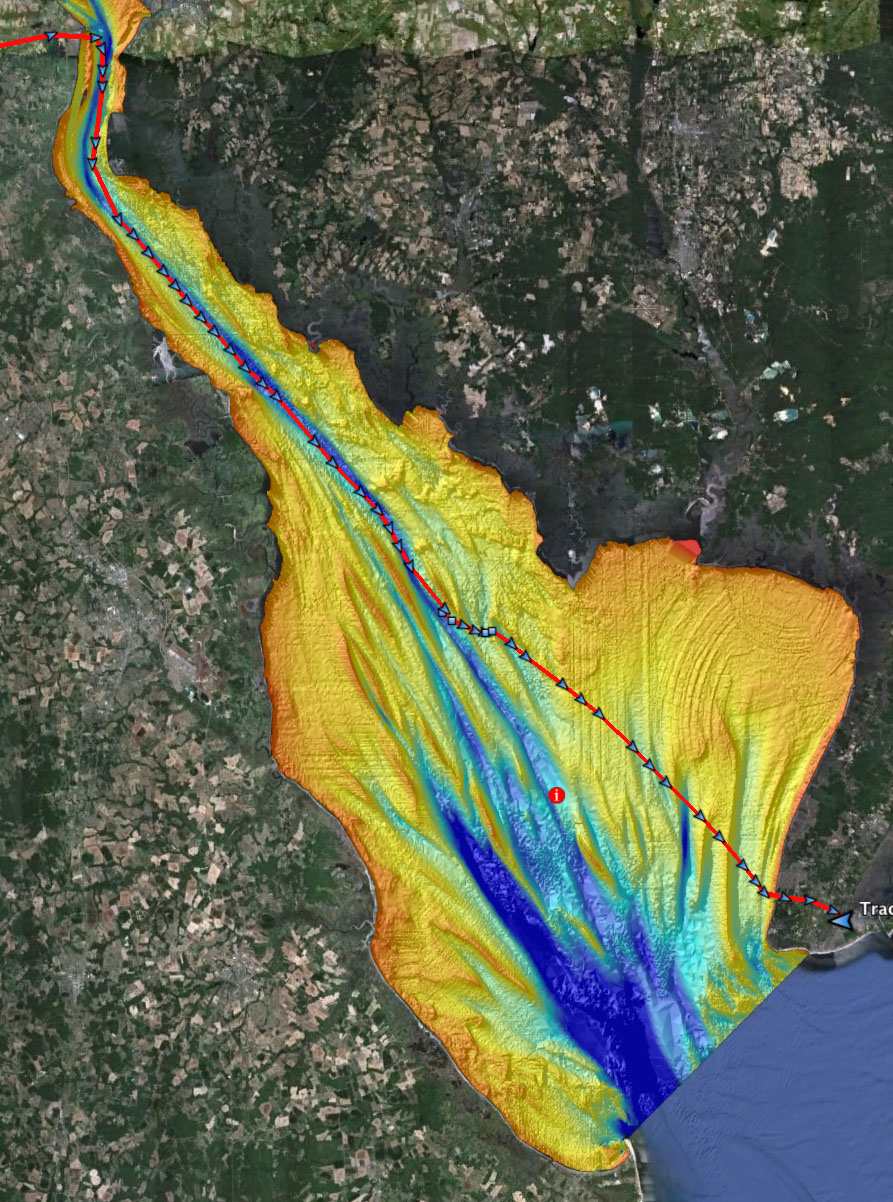

Relief map of the bottom of Delaware Bay, showing the route of Quintessence.

Relief map of the bottom of Delaware Bay, showing the route of Quintessence.

The main stem of the Chesapeake is fairly wide, deep, and flat. There’s a deeper channel that follows the old Susquehanna River bed, and shallows along the edges, but otherwise it’s pretty consistent. The basin of the Delaware, on the other hand, is miles and miles of shallow flats cut by a series of deep tapering canyons and steep ridges running the length of the it. The peaks of the ridges are just barely below the surface. There are places 6 miles from shore, for instance, where at low tide you can stand in water knee deep, while a short distance away it drops off to 50 feet. These ridges effectively corral herds of big waves in off the Atlantic into tighter and tighter blind canyons where they have nowhere to go but up. After shooting skyward, they bounce back and forth between the shallow shelves.

Now add the big wakes of enormous ships. The Delaware is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the country, second only to the mouth of the Mississippi. There is a near constant flow of tankers and cargo carriers up and down the Delaware, all throwing off wakes that also bounce back and forth from shore to shore.

Now add a crosswind, which sets up waves and chop moving in yet another direction across 25 miles of fetch.

Now add a strong tidal current, up to 5 knots in some places, flowing over that uneven bottom, tossing up yet more waves, and eddies, and cross currents.

Wave patterns overlapping other wave patterns create weird harmonics of waterborne energy moving chaotically in all directions.

What you have when you add all this up is a big ugly mess. Wave patterns overlapping other wave patterns create weird harmonics of waterborne energy moving chaotically in all directions. Momentarily they may cancel each other out, and you’ll have a few seconds of flat glassy calm. Seconds later, those same patterns will amplify each other into huge haystacks that seem to come from nowhere and everywhere at once, tossing even moderately sized boats from their rudders onto their bowsprits, only to suddenly disappear again. Lather, rinse, repeat. This goes on all night and all day, varying only with the strength and direction of wind and Atlantic wave trains. It was into this maelstrom that we drifted on an outgoing tide on Monday night.

At first, after leaving the C&D Canal, we could stay well outside the channel, since there was deep water on both sides. As the river opens out gradually into the bay, though, the water along the sides becomes increasingly shoal, and we had to move closer to the channel. For hours we watched the big ships appear on the GPS screen with their long vectors, and once in view watched them closely until they passed, then started tracking the next one. The wind died down, thankfully, but it swung around from north to south, and now came nearly on our nose, so we sheeted in and fired up the engine. Past the nuclear power plant at Artificial Island we set a course that kept us just outside the shipping lanes, the buoys passing just to port. It was going to be a long night, so Paul and I left the watch to George and Jay, and went below for some sleep.

There are a couple of things you should know at this point. First, Quintessence is fitted out with a battery of modern electronic navigation systems, including a combination Chartplotter/GPS/Depthfinder/VHF radio AIS system with large displays that can be read from both the cockpit and the cabin. AIS is a system that transmits information about nearby commercial ships via VHF radio. When connected to a chartplotter, you can see what ships are in your area, what direction they are headed, and how fast they are going. In other words, it allows you to see if you are going to get into trouble long before trouble arrives. Very, very cool.

Second, Paul uses Quintessence hard, harder than her previous owners. Over the years he’s had to make design modifications to account for this. Some of these things were obvious problems for him that probably just never came up on casual sunny day sails. For instance, the fuel tank vents for the engine were located in a place where, in rough conditions, water would get sucked into the system, contaminating the fuel and killing the engine. He installed special filters in the fuel line to eliminate it until he figured out where the water was coming from. Once he realized the source, he fixed that, too, but something still wasn’t quite right. On the way from Philadelphia to Baltimore, the engine suddenly died. He got a tow to a marina south of Philly, and taking apart the fuel lines pulled out what looked like a gooey spider nest. He’d gotten pretty good at diagnosing fuel problems, but this was something different. They cleared the fuel lines, put it all back together, and continued on without incident, hoping it was just a fluke.

There was also a problem with the VHF radio. Seemed like it wasn’t broadcasting. He asked a mechanic at the marina to look at it, who yelled into the mic and suddenly it started working again. There’s a cutoff filter in those mics, sort of like a squelch, so they don’t broadcast ambient noise. Perhaps it was just the squelch. Not terribly reassuring, but it did seem to be working, so they carried on. Both systems worked fine for the next five days, including the race. That was before all the pitching and rolling during the race and, very soon, in Delaware Bay.

Some time around 7:30, Quintessence began to pitch fiercely, enough that it woke me up. Moments later, the engine whined and revved. In the dark I saw Paul leap from his bunk to the engine and remove the cover just as the engine died. With a flashlight he could see there was no water in the filters, but there was no fuel in them either. Something had clogged the lines again. On the GPS he could see we were drifting from our course along the edge into the shipping channel itself, now disabled, in the dark.

Chart showing the path between Joe Flogger Shoal and Cross Ledge.

We were entering the narrowest section of the channel where there was the least room to maneuver, both for us and for the large ships coming our way. To the right was Joe Flogger Shoal, a steep ridge about 8 miles long. The middle 5 miles of it is only 3 to 5 feet below the surface. To our left was Cross Ledge, a shorter ridge just as steep, which for the next mile and a half was only 3 feet below the surface. Quintessence draws 5 feet. The tide carried us slowly into this narrow flooded canyon, and the wind, barely blowing against the tide, was pushing us toward the middle of the channel and beyond that toward the shallows of Cross Ledge. It was this narrow canyon pushing up the water into big waves that caused all the pitching, that killed the engine in the first place. Now it was hemming us in on both sides, setting us up like a lone pin in a bowling alley.

Things happened quickly at that point. For the moment we seemed OK. No ships showed up on the chartplotter. George was on the wheel, trying to keep our nose into the wind to minimize drifting. Paul got on the radio to notify the Coast Guard of our situation, and then call for a tow service. He called but there was no response. He looked at the chartplotter, which was still blank. Then we all saw the lights of ships coming our way. If those ships didn’t show up on the chartplotter, something must be wrong with the radio. Paul tried hailing the ships to warn them we were in the channel and couldn’t maneuver, but still nothing. He grabbed a spotlight and gave it to Jay to shine on the sails so the ships could at least see us, then grabbed a backup handheld radio and gave it to me to try and call the ships while he worked the main radio.

I felt like an idiot. I didn’t know how to work the handheld, couldn’t even find the call button in the dark.

I felt like an idiot. I didn’t know how to work the handheld, couldn’t even find the call button in the dark, and didn’t know how to say where we were if I did. The only thing I knew how to do was sail and take pictures. It wasn’t the best time for taking pictures, so I handed the radio back and started trimming sails. Without any forward motion the rudder was useless. While Paul worked on the radio, and Jay worked the spotlight, I loosened the sheets to get a little power so George could at least steer, and maybe give us a some control over where we were going. There wasn’t much wind, and it was coming from the wrong direction, but it was something, and it was the only thing I could do to help.

About that time the radios suddenly came to life, and we could hear the pilots on north and south bound ships talking about us. A whole string of ships now showed up on the chartplotter. Apparently, they had heard at least some of Paul’s broadcasts, knew what was up, and could clearly see our sails spotlighted in the dark. They were staying to the far side of the channel to give us as much room as they could. Paul switched to his cell phone and got a hold of BoatUS and gave them our location for a tow. They said it would take two hours for a boat to reach us, and would notify the Coast Guard.

The good news is while all this was happening we drifted out of the center of the shipping lane to the other side, just outside the marked channel. The bad news is we were a lot closer to Cross Ledge, close enough to see it in the dark – at least the churning water over it. We were finally sailing, if just barely, at a couple of knots. It didn’t stop our drift toward the ledge, but slowed it a bit, and we were moving a little faster down the channel. If we could just hold our course high enough we could make it to the end of Cross Ledge. Beyond that there was deep water outside the channel, and we’d be out of imminent danger, at least of running aground or getting run over. We had over a mile to go. As Paul said later, this was the one place in all of Delaware Bay where we had no choice but to motor in the channel, and that’s where the engine failed. The worst possible place. A stretch of water so dangerous it has been marked by no less than 4 lighthouses.

Detail of relief map.

For the next two hours we all worked at getting through. I tried to squeeze what there was out of the dying wind. Paul monitored our progress, trajectory, and the changing water depth on the GPS. George and Jay searched the night horizon for signs of ships, kept a close watch on those advancing north and south, trying to gauge any possibility of collision.

Looking ahead on the charts, Paul saw the end of Cross Ledge was marked by the ruins of a lighthouses, long abandoned. It bore no light or markings, was just dark rubble and a stone platform sticking up out of the water. We had to get past that without hitting it, and the first challenge would be to see it in the dark, in time to avoid it. Funny that something built at such great expense to warn ships of a hazard should be allowed to become a hazard itself. Why not put a damn buoy light on the thing?

At last we spotted the decapitated silhouette of Cross Ledge Light against the night sky, but Paul determined we were on a path that risked running us up on the rocks. We would have to tack, taking us deeper into the shipping lane. If we got into the channel and the wind died, we’d be sitting ducks.

With an all clear from Jay and George at a break in the shipping traffic, we made one short tack back to the channel, as far as we dared, then stalled. We reversed the rudder as Quintessence drifted backward, and we held our breath as she slowly came about, at last easing again onto a starboard tack. It was just enough to get us around the light and into open water.

Entering Cape May Harbor behind the tow boat.

Entering Cape May Harbor behind the tow boat.

When the tow boat arrived, we learned the radio had been broadcasting and receiving intermittently. Paul’s initial calls went out and were heard, but we could not the replies. The radio cut out in both directions as we communicated with the tow operator, and we switched full time to the handheld. Paul crawled out on the bowsprit to attach a rope bridle for the tow. One of those weird wave harmonics hit, and he was dunked several times as the bowsprit went under. He held on until the next calm and quickly got us hooked up.

With the bridle to the tow boat secured, we had a three hour tow across the bay to Cape May Harbor. This required vigilant steering the whole time through rough water, to prevent the bridle from damaging the pitching bowsprit. It was 2 am before, exhausted and suffering an adrenaline crash, we made it through the Cape May Canal to a slip at Utsch’s Marina.

The tow boat operator was quite a character, both a master at maneuvering the tow, and generally in a pretty foul mood. He zigzagged both boats through a maze of docks and pilings, and glided Quintessence gently into a slip like magic. I had a chance to chat with him a bit while he stowed the tow gear. He would only get a couple of hours sleep before heading out again to tow a houseboat across Delaware Bay, which explained his foul mood. He said he had spent his whole life in the area around boats, and would rather go 10 miles out into the Atlantic in a storm, at night, than cross Delaware Bay on a sunny day.

Tuesday morning was beautiful, of course. George and I were up at sunrise. Jay, knowing there was nothing to do for several hours, caught up on some much needed sleep. Paul, not surprisingly, woke up with a headache.

I killed some time shooting video of Cape May Harbor, which I’ll post in a day or two, and we went for a fine breakfast at a local diner. It’s a pretty place, Cape May. I’d like to go back and see more of it.

The weather for the outside run up the coast to Barnegat Bay was looking pretty grim. A front coming in. It would take at least a day to sort out the engine and radio problem, and by then it would be too late to get ahead of it. Heavy seas and 30+ mph winds were expected to last through the weekend. Paul and Jay would stay with the boat and take care of maintenance while waiting out the weather. Maybe visit friends on the A.J. Meerwald in its home port nearby.

Boat mechanic – Utsch’s is a full service marina.

Boat mechanic – Utsch’s is a full service marina.

George and I had less fluid schedules. George rented a car and dropped me at the nearest train station so I could get back to Baltimore. Sadly, the view diminished dramatically from that point on.

I talked to Paul later when he got back. They were in Cape May for several days waiting for the weather to improve. In the meantime, he determined the connectors between the radio and the antenna, down at deck level, were getting submerged when the boat was rail down, and simply corroded to make a partial sporadic contact. Another symptom of hard use. Cleaning and reseating the connections fixed the problem, but he’ll rewire the whole system over the winter.

He also had all the fuel pumped out of the tanks, and found bits of slime and sludge swirling around in what came out. Algae was growing inside the tanks, which got knocked loose during all that pitching in the Bay, and that’s what was clogging the fuel lines. Turns out this sort of fuel problem is fairly common, and not easily solved. Diesel fuel breaks down steadily, and is a growth medium for all sorts of microbes. This is hastened by the presence of water (hello, we’re talking about boats here). When fuel tanks are emptied and replenished regularly, as it is on power boats, the problem is just minimized. But on sailboats the engine is only used intermittently, and the problem becomes a problem more often. He plans to install a filtration system that will recirculate the fuel constantly, and hopes this will keep the process manageable.

Anyone who teaches safety on the water will tell you that all systems break down eventually, and always at the worst possible moment. You must assume failure, and plan for it. Through training and experience, Paul was prepared, and that kept us out of serious trouble. He had two radios on board, knowing one could fail, and knew how to use them both (I’ll be studying up on this). He had a handheld GPS and paper charts in case the whole electrical system went down. He had a spotlight ready and knew how to use it, making us visible to commercial traffic. He also carries a SPOT satellite tracking system, which for about $100 a year shows the boat’s current location at all times for both family and emergency crews. If everything else failed, and the situation warranted it, we could have pushed one button on the SPOT tracker and summoned a tow or even emergency rescue to our exact location.

It pays to be prepared, and was a good learning experience. And I, for one, won’t make any effort to go sailing on Delaware Bay any time soon.

Worth waiting for! Quite an epic experience from day one. Murphy’s Law strikes again. Remind me to tell you about the Bay Bridge story some day. Your story may bring back some old nightmares…

Not sure I want to hear it . . .

Whew. That was a close one.

Thanks for taking the time to create this Delaware Bay story, and all the other chapters on your website! Your photos and your writing have earned top place among my bookmarks. It was a great pleasure to meet you in Portsmouth after the GCBSR.

I have had my share of misadventures on the Delaware so this chapter had special meaning, particularly the relief maps.

Your whole series on the GCBSR is worthy of publication.

Hey Al, really wish I could have talked with you more in Portsmouth. Maybe Paul can arrange to get us in the same place again soon.

Hi Barry…..Good idea. Come on up to Mystic Feb. 3rd-4th to the American Schooner Association Annual Meeting. Or just head up here to MA anytime…. we’ll furnish digs and show you around Gloucester.. If you come next summer we’ll sail around a bit. We have wind and you won’t be melting.

Regards,

Al

Sounds great, Al. Assuming if I freeze in February, might be nice to do a little melting by summer.

I just found this blog entry trying to find out if I could sail my 14 ft Javelin from the C & D Canal over to Cape May. I think your entry certainly answered my question!

Thanks for the experience!

Thank you for this well written cautionary tale! We have a 1965 35ft Alburge and had thought of taking the kids from Baltimore to Lewes. I think we will plan a Chesapeake Bay cruise for next summer.

Fascinating story. Just bought a home in Cape May and keeping my 25 ft Donzi Regatta in Wildwood. I have been boating in the Hamptons since I was 12 and know the waters pretty well, the back bays, i.e. the Peconic, which is the largest bay in the country and can get rough also. I am a little hesitant to go cruising in the Delaware after seeing so many deep six ships there. Thanks for the info as for Cape May can be tricky and the surrounding bays also. Any more advice would be helpful. Safe Boating!

Great story ! had me clinging to the mast !