Oyster Farm – Franktown, Virginia

I did not account for reburying the family cat.

When MASCF got cancelled due to really, really bad weather for only the second time in 25 years (talkin to you Joaquin), a number of us found ourselves with boats and gear loaded with nowhere to go. We organized a consolation trip to the Eastern Shore within two weeks – four days of camping and sailing near Crisfield.

Normally, the night before a trip I spend packing and loading; which makes it easier for a no-so-early-riser to coffee up and get out the door at dawn. But mid-afternoon, I got a call at work saying something had dug up our recently deceased cat. Terri was clearly and understandably upset. She was an old and incontinent cat, and getting feeble. When the cancer came we realized the end had come, which is never an easy decision.

I guess it’s a dad thing. I remember as I was a boy when our old dog died my dad had the job of burying her. Through the upstairs window I could see his shoulders heaving as he shoveled and wiped his eyes and wept and shoveled.

Now it’s my job is to do the digging. Always alone, no ceremonies; just me with a shovel and our former pet together in a quiet place in the woods. It’s a veritable cemetery there now – dogs, cats, mice, hamsters, birds, etc.. I’ve lost track of them all. So I have a lot of experience now.

This is the first time one of my burials did not take. Nature has steadily regained ground over the years. We have bats, foxes, owls, swifts, snakes, possums, skunks, deer, even signs of a bear, and all but the bear (thank goodness) live in or around the house. Surely there are other critters we don’t even know of. Kitty had been in the ground three weeks before something took enough interest to dig her up. Nature red in tooth and claw.

So I spent the evening reburying the cat, and armoring her grave against marauders, instead of packing. Which means I am late leaving in the morning.

Again.

The sun is high by the time I cross the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel. It’s a clear day, and the view is beautiful. Up the Virginia end of the Eastern Shore, past Cape Charles, I hang a left down a nondescript country road. It runs along a ripe cotton field, the bolls stark white in the bright sun, then past soybeans where a combine is running, trailing a huge cloud of dust. Rows of chicken houses. The pavement gives out and the road turns to sand, winds past some nice frame farmhouses, then doglegs along the waterfront with marsh on both sides.

I’m looking for the Shooting Point Oyster Company, which is supposed to be down here somewhere. I promised to bring fresh oysters – a tradition at MASCF on the first night – and I knew this place was sort of on my way. I called the day before to see if I could pick some up – these small oyster farms only harvest on certain days, and normally only do wholesale. Tom answered the phone and said sure, come on down. At the bridge I called again to say I was running late. He was just heading out in the boat to for a load, but somebody would be there.

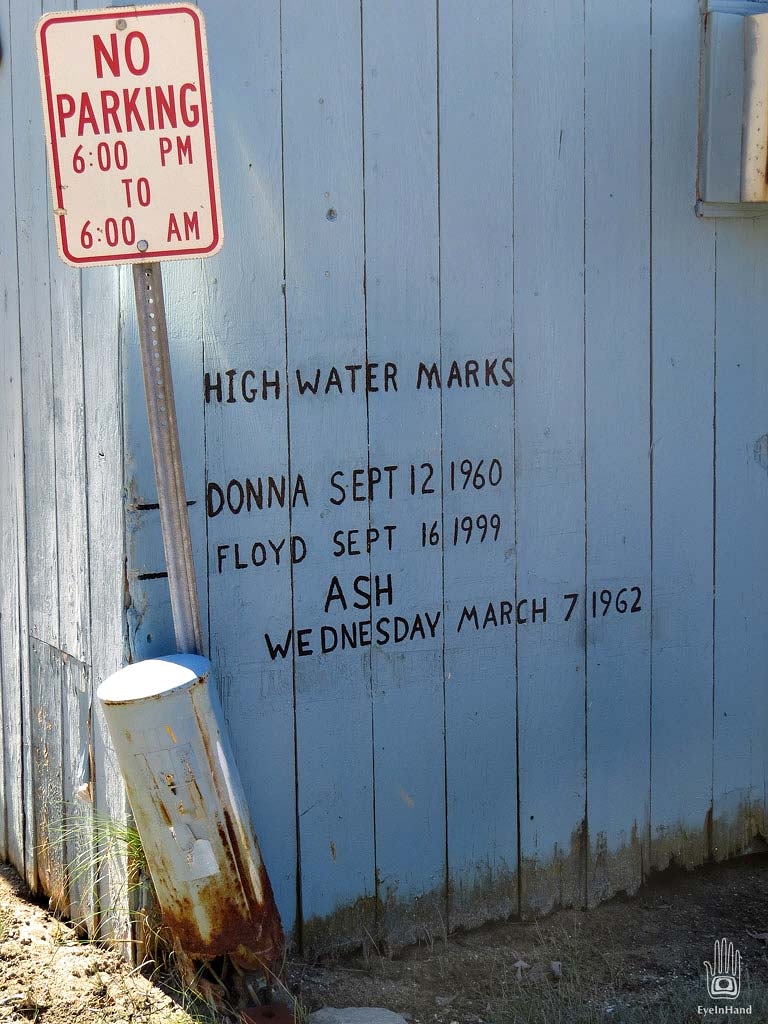

Along the water are a few old buildings and docks, and what I guess is Tom’s boat – there’s a lift mounted on the deck. The buildings are painted sky blue. The corner of one is labelled with the high water marks of several memorable storms. Some men are loading crabs into a refrigerator truck.

I go a little farther and come to what I believe is the address, but there’s no sign. It’s a farmhouse, and there’s a small garage-size building out front with the sound of machinery running inside. There are piles of waterman’s gear scattered about – crab buoys, cages, nets.

I park and wander over to the open bay door. A huge Chessie leaps up from behind out of nowhere and nips my shoulder, just as a strapping young guy in hip boots and foulies walks out. After making friends with the dog and confirming I’m in the right place, he says it’s his first day here, but he’ll go up to the house to check with Tom. He strips out of his gear and we walk across the yard together. He says he used to harvest the clams, but now is helping out with oysters, and is still learning how things work in the shop. Tom, who I talked to on the phone, apparently owns the operation. He comes out and shakes my hand, gives the young guy the order tickets and instructions. I ask who I should pay, and Tom laughs, “Oh I don’t know, somebody will take your money,” and waves.

Washing Oysters

We walk back to the shop and the young guy disappears somewhere in back. There’s a piece of stainless steel equipment making all the racket. It’s a big drum fed by a conveyor from a bin full of fresh oysters. They feed up the belt and tumble around in the drum where they’re washed and tumble out the other end. I’ve seen potatoes cleaned in the same sort of contraption. The Chessie is now my best friend, and won’t leave my side, keeps bumping against my legs for more scratching and rubbing.

When the guy comes out he has a whole case of 100 oysters harvested that morning for $40. Shooting Point Salts. He packs them in ice in a plastic bag, and the package fits nicely in the cooler I brought for the purpose.

I pay in cash and give the young guy a tip for his trouble.

It’s too late to do more than set up camp before dark. The guys who arrived earlier are coming back from a sail. That night around a fire we crack open the oysters with beers and cocktail sauce and lemons, or slurp them straight. Very plump and very salty like the ocean. We barely make a dent in the case. We’ll have oysters for days.

Some great tips and sound advice for oyster eaters – newbies and aficionados – can be found here:

The New Rules of Oyster Eating