Visible progress is entering a slow phase as I take on a couple of tasks that require a lot of mental horsepower. Sometimes I get tired and just have to sit and think, or take a break from thinking, and then interesting things start to happen.

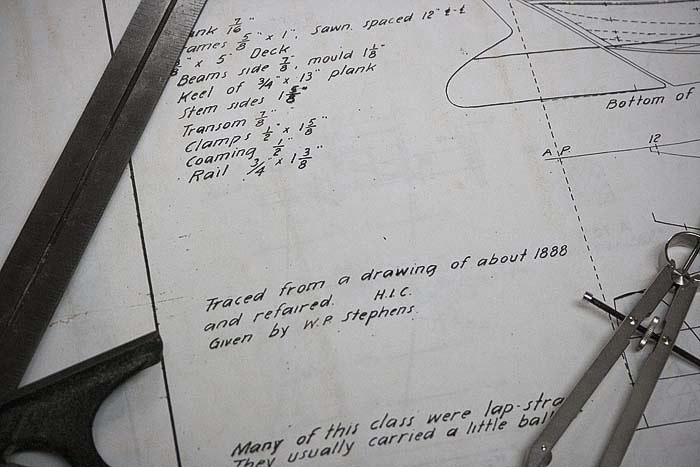

One of the odd things about spending so much time In the shop with these old style boats, old tools and old drawings, is you get a little unhinged, or rather, unstuck in time. I sit down at the drafting table, with the warm wood of the hulls glowing under the lights, and study the Chapelle plans more, looking for clues on how to proceed. Though these are copies, the original plans are old, dating from the early 1930’s, and those were made by hand from originals that were earlier still. Knowing that, and seeing the handwritten notes and sketches scrawled across them, sort of transports you back in time a little, as would an actual artifact from that period.

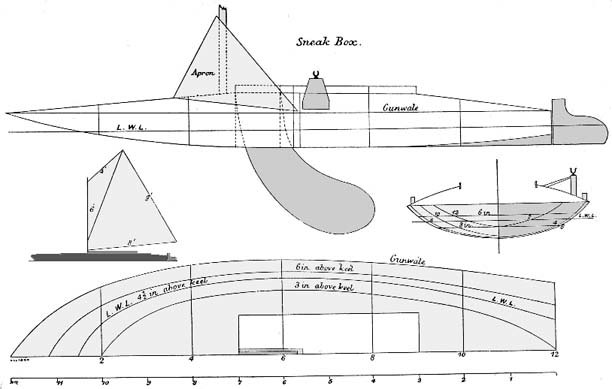

A few weeks ago I read a book called Four Months in a Sneak-box, written in 1879 by Nathaniel Bishop. Bishop was an adventurer of sorts who walked across South America, and shortly after travelled down most of the Atlantic Coast in a paper canoe. He wrote books about both trips that were popular in both America and Europe. His third and last adventure was to travel over 2600 miles down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and along the Gulf of Mexico, from Pittsburgh to Cedar Key, Florida, in a Barnegat Bay Sneak-box. The Sneak-box was the elder sibling of the Melonseed, native to the same region and builders, and looked even more melonseed-like. It was about the same size, had the same rig and basic design, but the hull was flat, oval shaped and more fully decked, like a teaspoon with a lid.

Sneak-box Plans

Bishop’s observations and commentary give a kind of snapshot of life in America in the late 1800’s, unusual in it’s view from a small boat. The rivers then were like floating communities, with cobblers, carpenters, blacksmiths and various tradesmen operating from workshops on rafts set adrift, and a host of people, even whole families, living on shanty-boats floating downriver. He dodged steamboats plowing up and down the Mississippi, escaped river ruffians, dined with plantation owners along the banks, and skirted the fringes of the Florida wilderness. There are a number of oddities, too, like a Captain Boyton, who devised a rubber life suit that he wore swimming, paddling himself feet first, kayak style, down various rivers of the world, following behind Bishop down the Mississippi the same year.

Captain Boyton in his rubber life suit.

Bishop’s book interested me initially because the Melonseed was derived from the Sneak-box design, modified to be more versatile, to improve handling in rough water, and it dates from around the same time period as the travelog. On the Chapelle Melonseed plans from the Smithsonian is a hand written notation along the side that reads “Traced from a drawing of about 1888.” While studying the plans, or just taking a break, I keep coming back to that note and, like Alice falling down the rabbit hole, I tumble back through that tunnel to another century.

Certainly, reading Bishop’s book has contributed to the effect, but an odd thing happened the other night that compounds it. When Terri and I were fooling around taking pictures, and she climbed into the North hull for a photo, there was a moment just before I snapped the shutter that was like a bell ringing. I didn’t know what it was, but there was something familiar about the image. Then a few days later the connection dawned on me: A print, now in a closet, once hung in our dining room from a painting called “The Lady of Shallot” and the two images looked oddly similar.

The Lady of Shallot by John Waterhouse

Terri in North by Me

What is even more odd is, when I dug up the picture, I saw that the painting was made in 1888, the same year as the plans for the boat in which Terri is sitting.

This strange harmonic resonance, along with the book and the date on the plans, all have me thinking about when these boats were originally made, by that small group of builders in a relatively small area along the Atlantic coast. What a different world it was then – in 1888 the American Flag only had 38 stars. The more I think about it, the more I realize what a truly amazing period of time that was, and what it must have been like to live then, to see the world around you transforming before your very eyes. In the span of a single lifetime the world would be a completely different place.

The end of the 19th Century was the end of the Victorian Era, when the flame of the British Empire still burned bright around the world. Human history had plodded along slowly. In many ways it pretty much remained the same for eons, essentially since the domestication of animals. But the American experiment in Democracy had survived its own Civil War, and that idea – that a nation could be ruled by it’s people instead of royalty – was spreading fast across continents. One by one, nations ruled by Czars and Kaisers and Kings and Emperors, were taken over by an increasingly powerful Middle Class, and the centers of power shifted from bloodlines of the aristocracy to political movements, corporations, cartels and other group alliances. Some transformations were peaceful, and some were not. Bismark had only recently united the teutonic tribes of Germany into a single country by stoking flames of nationalism and military aggression, setting into motion a series of events that would eventually lead to two World Wars, and through that a complete realignment of the world political map.

The contrast between the old world and the new was striking. For instance, here are pictures of contemporary leaders of the time: Kaiser Wilhelm, Emperor of Germany, and Czar Nicholas II of Russia with a cousin, and Queen Victoria (all related, by the way).

And here in contrast are some US Presidents of the same period: Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland and Teddy Roosevelt.

Changes in other ways were equally striking. Machines were beginning to replace the manual labor of people, who moved from the countryside to cities in greater numbers, where they would work in factories instead of fields. The Arts & Crafts Movement, like Art Nouveau that followed it, was both a rebellion against the opulence of the Victorians, and a rejection of mass produced goods coming out of the factories. It promoted a renewed appreciation for handmade craftsmanship and natural forms in art, material objects, and architecture. But they would be short lived – the first “skyscraper” was built in Chicago in 1885, an insurance building.

Mechanization was taking over in many ways. Waves of immigrants were arriving by steamship, and the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886 to welcome them; but from the ships they would first see Coney Island, one of many resorts and attractions financed by railroads along their lines to increase travel by rail.

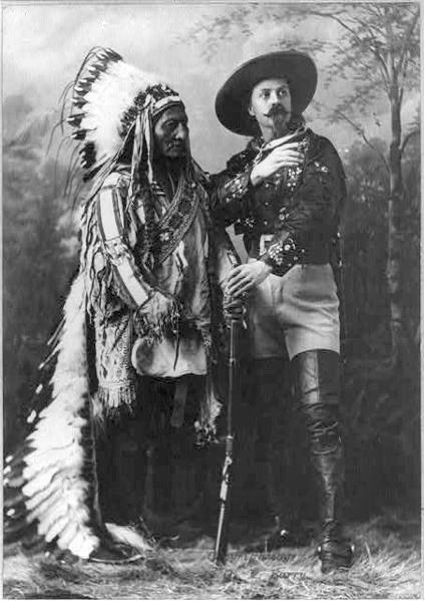

Railroads now spanned the continent, helping bring about the near extinction of the American Buffalo, and the Plains Indians who depended on them. Herds that numbered in the millions were reduced to only a few hundred scattered in small groups. The West was no longer wild, but a nostalgia for it lived on. Buffalo Bill took his Wild West Show on a worldwide tour re-enacting events from the recent past, like Custer’s Last Stand, with a touring company made up of the actual living remnants. Famous people like Sitting Bull, Wild Bill Hickok and Annie Oakley performed for huge crowds everywhere. They performed for five straight weeks on Coney Island, just a days sail up the coast. In 1889 they toured Europe and performed for the Queen of England. Two years after the Melonseed plans were drawn, Sitting Bull would be killed by Indian agents under orders from the US Army, and this would be followed only weeks later by the Massacre at Wounded Knee.

Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill in 1885

Suddenly Gatling guns and other forms of mechanized warfare were being used against people of less industrialized cultures with devastating effect. Reluctantly, the British Redcoats stopped wearing red, for now long range rifles and artillery could be used to pick them off from a great distance, as soon as they were visible. Camouflage, tanks, and guerrilla warfare became a necessity, replacing the brute force foot soldiers of standing armies – the era of Napoleon was over.

The age of sail was ending, and whaling as a commercial enterprise was so depleted that by the late 1800’s it was only viable by steamship, far from the New England towns that were founded on it. As a result, whale oil for lamps and fuel was steadily replaced by petroleum, already produced at the rate of 35 million barrels in 1888. By the 1880’s, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company – through acquisitions, collusion with railroads and suppliers, and cutthroat competition – controlled a monopoly on the entire industry, destined to become the wealthiest corporation in history.

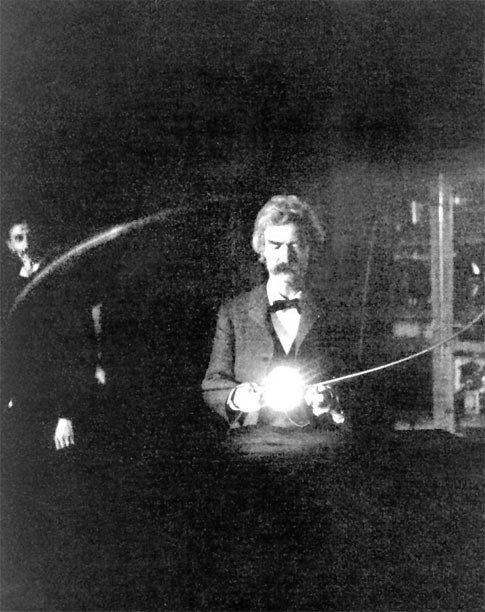

Wondrous inventions of all kinds were coming one after another, and each one seemed to bring about another major change. Thomas Edison, was inventing (or taking credit for inventing) all kinds new wonders, such as lighting up New York City just up the coast with electricity. In an odd marketing campaign, he was also electrocuting elephants in a vain attempt to scare people away from using the more efficient electrical system invented by Nikola Tesla. The demonstration killings led to invention of the electric chair by employees in his labs in 1888, for executing humans. Tesla patented his alternating current in 1888, and we still use it today.

Bell had already invented the telephone, and radio was not far behind. In 1888, George Eastman registered the name “Kodak” along with a patent for a handheld camera that used roll-film, making photography available to the masses. A bicycle craze was sweeping the nation, and everyone with a little extra cash wanted one. Taking advantage of this popularity, the Wright Brothers would in 1892 open a bike shop, making enough money from the venture to finance their experiments in flight.

A Benz “motor wagon” of 1888

In the meantime, someone would put a petroleum powered internal combustion engine on a bike, making the first motorcycle. Shortly after that, the same would be done to a carriage. As a result, in Germany in August of 1888, Berta Benz, in a “motor wagon” invented by her husband Karl, drove with her two sons from one town to another to visit her mother, a distance of 60 miles (repairing it herself several times on the way), and took the first long distance trip made by car. Albert Einstein was then nine years old.

The end of the century became known as the Gilded Age, because rapid industrialization was concentrating enormous wealth and power in the hands of a relatively small group of entrepreneurs, the most ruthless of whom became known as “Robber Barons.” People like Rockefeller, Carnegie, Vanderbilt, Duke, Frick and Stanford amassed unprecedented fortunes and built American palaces with the proceeds.

The era would be accompanied by social changes, too, giving birth to the labor and women’s rights movements. Communism would grow it’s roots in the decay of both the aristocratic royalty of the old world and the opulent decadence of capitalism, made possible by the harsh poverty of countless laborers in a sort of new feudalism. Prohibition was taking hold, and the growing Temperance Movement would spur the introduction of non-alcoholic drinks such as Coca-Cola, which contained cocaine, and were sold as patent medicines “for medicinal purposes.” Opium and it’s derivatives were a common addiction worldwide. As a result of the Opium Wars, almost a third of the adult male population of China was addicted.

Sigmund Freud

In 1888, Jack the Ripper murdered his first victim in London, two years after Robert Louis Stevenson wrote The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. In the same year, Sigmund Freud abandoned hypnosis, a popular stage entertainment at the time, for “the talking cure” which would become the basis of psychoanalysis.

Mark Twain playing with lightning in Tesla’s lab.

All these radical social and economic changes were manifested in the world of art and culture. Authors like Whitman, Tennyson, Dickenson, Emerson, Melville and others of their generation were dying off. By 1888, Mark Twain had completed his most well known works, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, and a gritty realism began to take hold on both continents, in both literature and the visual arts.

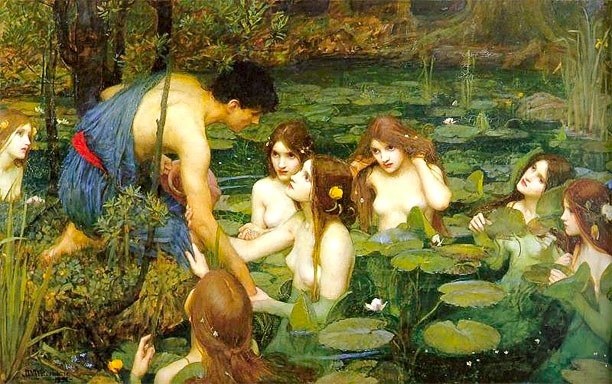

For instance, the painting of the Lady of Shallot, by Waterhouse, was part of an old world aesthetic that still clung to a romanticized view of the time of kings and myth. But new schools of aesthetics – the Impressionists and those that followed – were gaining acceptance, and they were influenced by discoveries in the mechanics of light and vision, and the advent of photography. Realism began an assault on myth.

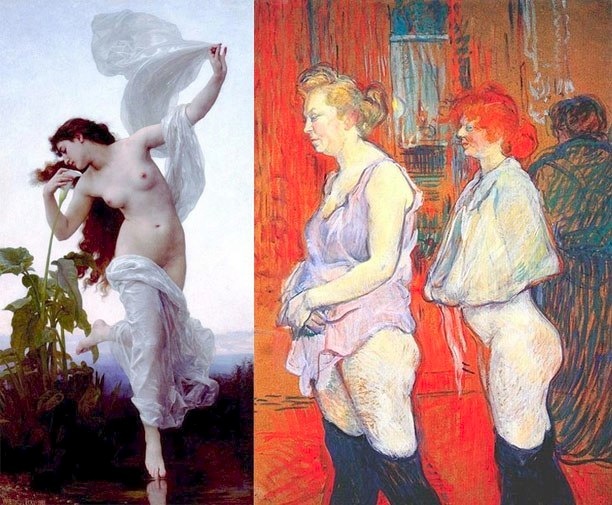

The old guard in Academies and Salons of Paris and London fought to keep control of the art world, rejecting modern paintings that appeared to show real women in the nude painted in a contemporary style, for example, but rewarding those showing nude women in scenes from mythology in a classical style. In fact, the Impressionists, and artists like Whistler and Manet, initially had to show their works in the Salon des Refusés, literally “the gallery of rejects.” The differences between old and new is, again, no less than startling.

Bougereau’s “Aurora” and Toulouse-Lautrec’s “The Medical Inspection”

Artists like Waterhouse and Bougereau enjoyed the patronage of aristocrats in salons and museums with paintings of nymphs and heros, while artists like Gaugin, Monet, Degas and others took their easels into bars and pool halls and parks and the countryside and painted life around them, of real people and scenes of contemporary life, ultimately gaining the patronage of the new upper class from working backgrounds with their newfound wealth.

Van Gogh “The Night Cafe” 1888

In 1888, Van Gogh was entering a prolific period in Arles that would lead him to both madness and greatness. Though now famous, Whistler was bumping along in bankruptcy and ignominy before finally achieving redemption through associates like Monet, Rodin Toulouse-Lautrec and fellow American John Singer Sargent.

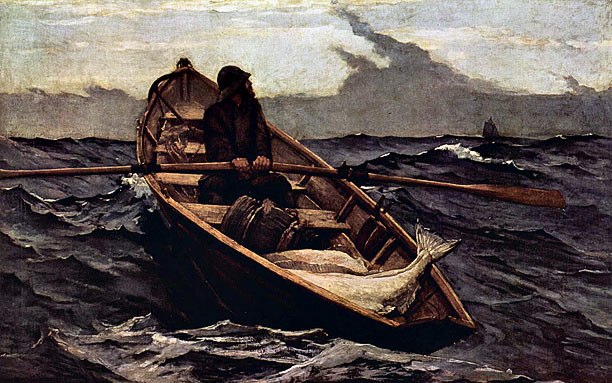

Back in the States, Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins were leading an American tradition of realism. And again, the contrast between old world and new is striking:

Draper’s “Ulysses and the Sirens”

Winslow Homer “Breezing Up”

Waterhouse “Hylas and the Nymphs”

Winslow Homer “Fog Warning”

Eakins “Starting Out After Rail”

Eakins was fascinated by photography, and used it extensively in his studies for paintings. His experiments in photography, specifically animal and human motion, would influence Modern Art for decades.

One of Eakins’ “Studies in Human Motion” from the 1880’s

“Nude Desending a Staircase” by Duchamp in 1912

Eakins’ interest in photography and motion was derived from the work of Eadweard Muybridge, whose work in rapid exposure of sequential images would ultimately lead to motion pictures.

Muybridge’s “Cantering Buffalo” series set in motion.

It was a strange and sometimes fearful time. Comets hung in the sky for years on end. Planets were discovered. The Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883, the longest suspension bridge in the world. The first “jumper” commit suicide by leaping from it less than two years later. The world was changing, and the age of men was giving way to the age of machines.

The Brooklyn Bridge during the Great Blizzard of 1888.

In 1883, the volcanic island of Krakatoa blew itself up in one of the largest explosions in recorded history, so loud it was heard over 2000 miles away. The force of it sent shock waves and tsunamis racing around the globe. It blasted so much dust into the air that it darkened skies for a decades, steadily lowering temperatures worldwide. By March of 1888, a massive blizzard, “The Great White Hurricane of 1888” struck the Atlantic Coast, dumping 50 inches of snow from the Chesapeake Bay to Massachusetts. High winds caused drifts over 40 feet high throughout New England, burying houses and railroads, disabling entire cities. Hundreds of seamen lost their lives in that storm along the coast.

That blizzard particularly interests me, now. I imagine a boatwright working by kerosene lamp in his shop along the Jersey shore in 1888. With the storm raging outside, snowed in with nothing else to do, maybe he was feeling a twinge of his own mortality and the passing of an era, when he decided to draw out the lines of a fine little boat sitting half built across the room. And maybe, because of that storm those plans have arrived here, where 120 years later someone else is building another boat very much like it.

Seabright Skiff on the Jersey Shore, 1887

melonseed skiff, mellonseed skiff, melon seed, mellon seed

Barry, this is an amazing post, I love how you’ve woven a tapestry from the tangents.

Monday, October 12, 2009 – 08:44 PM

Thanks, Thomas. Nice to know someone else likes history, too. My guess is the average reader doesn’t last to the end of that post, so it’s good to hear someone not only made it to the other side, but even liked it. And there’s so much left out.

Cheers,

Barry

Monday, October 12, 2009 – 10:23 PM

Barry, what a wonderful read. North is looking great. As you know, Errant One and I have spent many a night together on the Chesapeake camping and doing long sails. We still haven’t completed a circumnavigation of the DelMarVa peninsula but it will happen once I can string enough days off together. Your blog so reflects hours of my own thoughts but you weaves a tale far better than I ever could have put together. Well done and thanks for sharing

Barry, this is a magnificent “rumination”. The juxtapositions you present are poignant and thought-provoking. The older I get the greater my fascination with history which – as your posts so beautifully illustrates – comes to life when you shine an inquisitive light on concurrent details of the past. And such a wonderful way of connecting history to your project! Thank you! — BTW, are you familiar with “Sapiens” by Noah Yuval Harari? It is an account of the history of humankind by a historian who asks uncommon questions.

Thanks Christoph. I really enjoyed writing it, and it’s nice to be reminded to go back and read it again.

I’m not familiar with that book, but based on your comments I will look for it. History is definitely not boring, only some tellings of it are.