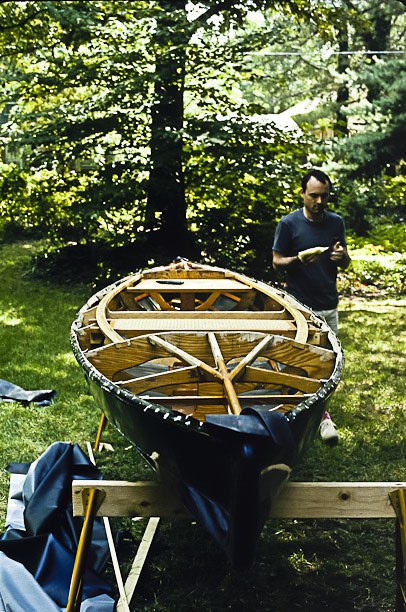

Mike with Odin, circa 1985

When you spend long days in the shop, on tasks that don’t require much thought, your mind tends to wander. Since I’m working on boats, that’s where my mind goes, and I often take long mental journeys in boats from the past. Something happened earlier this year that reminded me of the second boat I could actually call my own, and I’ve been thinking of it a lot lately. The first boat was great, too, but it’s the second one that’s really been on my mind lately. Like the first boat, this one I shared with a friend, and that contributed a great deal to all the memories connected with it.

It’s an odd thing, but in a lifetime of playing in boats, the ones I had the most fun with were also the cheapest. There is a definite correlation between how little money and worry you put into owning a boat, and how much pleasure you get out of using it. Less is definitely more. The boats I had the most fun in when I was younger were cheapest – this one was free.

It was found by a hunter hanging 20 feet up a tree, way back in the woods, apparently left there after a flood. No telling how long it had been there. For the short time it was mine to use, I shared it with a buddy named Mike Harrell. Given it’s odd provenance, we called it Odin – a norse god who hung in a tree for nine days.

Neighbors said late every Fall he would slaughter a hog and leave it on a table in the cold, unheated central hallway, then live off that all winter.

Back in the 80′s, when my dad’s parents moved from their place on the Bay, they bought an old farmhouse on 20 acres back in the country, bordering the Willis River. The house was built in the early 1800′s, never had electricity or running water, heated only by a fireplace in each room. The timbers, over a foot thick, were hand adzed from old growth logs cut off the land, and were held together with wooden pegs. Walls were horsehair and plaster over split oak lathes, attached with hand cut nails that probably came upriver on batteaux from Thomas Jefferson’s nail factory. All the trim work, window sills, etc., were made with multiple passes of specially shaped hand planes, and the window panes were wavy hand poured glass. The house was definitely high style for the countryside in pre-Civil War days. The original owner was a Confederate colonel in the cavalry. Sunken graves surrounded the house, marked only by simple field stones. It was a very cool place, but suffered from a hundred years of neglect.

When my grandfather found it, a fellow lived there alone, named Elrod, if I remember. The last son of the last family to own it, Elrod spent most of his time sitting in an old school bus seat on the front porch. Neighbors said late every Fall he would slaughter a hog and leave it on a table in the cold, unheated central hallway, then live off that all winter, cutting off what he needed for each meal. There was a hand pump on the well, and an outhouse down the hill. Elrod lived like that quite happily, apparently, for about 20 years.

While inspecting the property prior to buying it, my uncle climbed up in the hay loft of the barn, above a huge pile of manure, and found, nestled among old hay and various animal droppings, a small dirt-covered boat. They asked Elrod about it. Hurricanes had not been kind to Virginia during the second half of the century. Some time after one of them, Elrod said he found the boat hanging high up in the trees near the river. He didn’t trust the water and wouldn’t use it himself, but was not a man to waste anything, so he dragged it home and stuck it up in the barn, where it sat for another 10 years. The boat conveyed, he said, along with the other rusty implements, manure, and leftover hay. (I personally shoveled that manure into the garden later, and we had the finest crop of corn and beans and squash that year that I’ve ever seen.)

My grandmother felt she had moved up in the world a bit since using an outhouse as a girl, so my uncle and grandfather and I spent a couple of years updating the amenities to make it more suitable for gentle ladies. Frequently, while working on one thing or another, my uncle and grandfather would bring up the subject of the boat in the barn, and how they thought I was just the sort of person to take on that project and make it usable again.

At the time, I had a ’67 Ford LTD I bought second hand for a couple of hundred dollars. It was as long as the boat, about the same vintage, and rolled like the waves, too. We lowered the wreckage of the boat down from the loft, I tied it on top and drove it home.

The boat was in pretty bad shape. Near as I can tell, it was a some sort of folding or kit kayak. Probably a Folbot. The entire top deck cover had been ripped off in the flood and, somewhere between where it started and where it ended up, the seats and some internal frames were torn out, too. Remarkably, the rest of the boat was intact. Still, the project was going to take some serious work. I needed help, and motivation.

Mike and I worked together on the night shift printing photographs in an old building on Broad Street in downtown Richmond. It didn’t take much to convince him to lend a hand. The idea was to fix the boat up and use it during the day when everyone else was at work. Even after he saw the boat he was still game.

We patched up the hull skin with rubber cut from tire tubes and replaced missing wood pieces, just guessing at what had been there before. For seats, we built frames and caned them for comfort. For the missing top deck, though, we were flummoxed. The hull was skinned in a kind of rubberized canvas, and we had no idea where to get more of it. We ended up with a length of black vinyl naugahyde from the fabric store, like you’d use to cover a cheap Lazy-Boy lounger, which both confused and amused the ladies at the counter when we explained what we needed it for. We glued it on with black roofing silicone sealant and upholstery tacks.

Within a month we had what seemed to be a respectable approximation of a boat. We picked up a pair of the cheapest paddles we could find, tied the boat on top of the LTD, and went looking for interesting water. (This was adventure in it’s own right, as the LTD didn’t have a working reverse gear, and we often drove down narrow dirt roads that dead-ended unexpectedly with no room to turn around.)

The boat was outstanding. It surpassed all our expectations, and excelled at the most challenging tasks we could come up with. It was, to this day, the most amazing paddling boat I’ve ever experienced. The low, wide profile was both dry and extremely stable – even though we sat high and comfortably near the rails, instead of down low in the bottom as originally designed. The rubber skin made the boat totally silent – it didn’t bang or scrape like a hard shelled canoe – and we delighted in paddling right up to all sorts of wildlife on every trip that never heard us coming. Because the frame was flexible, and the skin supple, the boat just slithered over snags and obstacles like an otter. We didn’t need water even as deep as the draft. Literally, a wet spot was enough. All we needed was a good head of steam and we could paddle right over an exposed wet log. We laughed out loud as we paddled upstream over beaver dams. It was without a doubt the best swamp boat I’ve ever encountered.

Because the frame was flexible, and the skin supple, the boat just slithered over snags and obstacles like an otter.

We took it to every swamp and bog we could find within 100 miles of the city, even paddled it to the middle of Lake Drummond in the Dismal Swamp. For two glorious summers we spent weekdays driving to new spots to try the boat, when we had the water to ourselves, then would get back to the city as everyone else was going home, and work past midnight basking in the glow from long days on the water. It was a great time.

Sadly, what made the boat so great for swamps made it less great for big, rough water. In the Fall of the second year, hurricane season, in high water after a storm, I broached against a rock in the James River, and in an instant the boat wrapped and snapped like a soggy popped balloon and a bag of splinters. A flood brought the boat, and a flood took it away.

That was roughly 25 years ago. In the time in between, Mike and I both moved away and lost touch. Working on these boats brought back all those memories, and I decided to look him up again. As it happens, he and his wife have a house back in Richmond, splitting their time between there and Brooklyn, NY, for work. We arranged to meet one evening after Terri and I spent a day scouting possible launch sites. Walking into their living room, the first thing that caught my eye was a photo on the mantle, of Odin, all finished and ready to go. I couldn’t believe it. I’ll have to ask him for a copy of that picture, as all the ones I have were taken before all the work was complete.

Mike is another one of those people I want to take out on the water again when these boats are ready.

Me, Mike and Amy on Church Hill in Richmond, circa June 2010.

melonseed skiff, mellonseed skiff, melon seed, mellon seed

An awesome tale. Odin, rest well.

Wednesday, July 13, 2011 – 12:49 AM

Thanks for that, Barry. A happy time for a couple of dreamers.

Thursday, July 14, 2011 – 11:34 AM

Amazing, and a boat to treasure.

It looks a well designed and well made craft, and if I may, I would like to use part of the story and some of the photographs in the next issue of Paddles Past, if I may.

What would be useful is to know the LOA, beam, and height of the boat at its highest point, if you have these details..

I think I would have used proofed cotton duck for the deck as this will allow the hull to breath, and could also be re-proofed in the event a little water trickles in.

It is not easy to determine which parts of the frame are original, and which parts you replaced – can you let me have these details?

I note you were using single bladed paddles – were these easy to use bearing in mind the margin of decking around the cockpit. Did you ever try the use of double bladed paddles, and if so, their length, and was it easy to paddle, bearing in mind that the boat seems wide in the beam at the centre.

My final question at the moment is: how were the stringers fixed to the frames, and were the frames made of marine quality plywood.

Tony

Alas, I don’t have any measurement details. These few photographs are the only documentation left.

We had very limited resources for information back in the days before internet search. I remember ordering a catalog from either Klepper or Folbot, whichever one was still in business at the time, just to look at photos for possible clues. Ultimately, we had to just wing it. We added the middle frame, made of marine plywood like the rest, the stringers around the cockpit, and the seats. All the other wood parts were original. I believe the stringers were glued and screwed.

We used single bladed paddles, and they worked great, especially since we sat up high in the boat instead of down on the bottom. Easier to use, certainly, in the confined and overgrown waterways where we took the boat, but even in open water we never wanted for double bladed paddles.

Thanks for your last. I shall need to get on with the information before me. Both Klepper and Folbot are still in existence, and a number of new companies have raised themselves abo ve the destitution zone, ie, Pouch, Feathercraft, Nautiraid – so there is still life in folding kayaks

Tony