At the dock and gatehouse we find for the first time, as we will for the next two days, that we have almost the whole island to ourselves. There’s no one here to greet us, take our entry fee, or oversee the exhibits. Dozens of park service vehicles are parked neatly in rows in a lot, empty. With all the DOGE cuts to National Parks, and everything here federally funded, there’s not even a ferry to bring people over from the mainland. We will not see a single Park Service employee in the entire two days we spend on the island, which is 20 miles long.

From the dock we walk a sand road through an arched avenue of live oaks. The nave of a living gothic cathedral. This, I thought, is what my art history professor meant when she said a forest is the inspiration for those arches and cathedrals. It was how you got Druids to become Christians.

Winding south, we come to the ruins of Dungeness.

The first American to claim Cumberland Island was General Nathanael Greene, a Revolutionary War hero who served with Washington at Valley Forge. In honor of his service, he was awarded land near Savannah and most of Cumberland Island. Greene died of sunstroke at his Savannah plantation, Mulberry Grove. His widow married their children’s tutor and they moved to Cumberland, where they built the first Dungeness – a 5 story tabby mansion so tall it was used as a navigation landmark. The site chosen was the packed shell ring on a bluff over the inlet, a site sacred to the native Americans for thousands of years prior. “Lighthorse Harry” Lee, Revolutionary War hero (and father to Robert E. Lee, the Civil War general) visited the estate, fell ill and died. He’s buried here. Dungeness, the mansion, burned in 1866.

Oddly enough, it was on Greene’s Mulberry Grove plantation where the cotton gin was invented. That bit or technology turbocharged the southern slave economy setting the national stage for the next big conflict, the Civil War. After that war, half the island was owned by Confederate General William George Mackay Davis, cousin of Jefferson Davis. Scrambling to make a living after the collapse of the Confederacy, Davis wanted to make a resort of the island, giving tours of the Dungeness ruins. But his son, Bernard, accidentally shot and killed his young son in a hunting accident on the island. Distraught, Bernard later killed himself. The combination of tragedies led Davis to sell his part of the island, to Thomas Carnegie.

The increasingly mobile industrial classes, like those who came before, fell under the spell of the Florida land speculators. Carnegie bought Dungeness Plantation, of which he had never before heard nor seen, in Georgia, where he had no connections, from a former Confederate general whom Carnegie had never met. But his wife read a glowing article about the place in a magazine while visiting Amelia on their yacht. Another triumph of marketing for my copywriter friends.

Thomas was brother to Andrew Carnegie. He was instrumental in building the vast family fortune that made them famous. When their consolidated US Steel was purchased through a consortium by J.P. Morgan, it was the most valuable corporation in the world, by far. Thomas purchased half the island from the distraught General Davis and gave it to his wife, Lucy, and began building a new Dungeness on the rubble of the old one. Designed by top architects of the time, it was a vast rambling affair, opulent with Tiffany glass and other elegant features, and remarkably was built and furnished in less than a year. Pittsburgh, with all the Carnegie Steel mills and forges, had become too polluted. Cumberland would be their healthy unspoiled new home.

Then Thomas fell ill and died.

His widow, Lucy Carnegie, hired her children’s tutor to manage the entire estate (there’s a couple of repeating patterns here, if you’re paying attention). William Enoch Page, the tutor, did an amazing job of this. Like crazy good job I won’t get into here – we’re talking water systems, electrical generation, elevators, food production, staffing, construction, etc., all of this back in the late 1800s. Leveraging the windfall from the sale of US Steel, the Carnegie holdings grew to encompass 90% of the island. Separate mansions were built for all of the married Carnegie children, with their spouses and offspring.

Greyfield Inn, originally one of the homes, is still privately owned and run by heirs of the family. We will see another of the homes tomorrow at the north end of the island.

After Lucy Carnegie’s death in 1916, the estate moved into a complex family trust and things began to unwind. Heirs lived in their own mansions scattered across the island. Maintenance of the big house and operations became more and more onerous.

By the end of the Great Depression, no one lived in Dungeness full time, staff and caretakers dwindled to a skeleton crew. A single gamekeeper was tasked with guarding the whole island. One night he shot at a poacher, striking him in the leg. Soon afterward, someone shot holes in the Carnegie yacht and set it adrift. Weeks later, fire was set to Dungeness and it burned to the ground, leaving a shell of thick masonry walls. The wounded poacher, a known vengeful troublemaker, was accused but never convicted.

We stroll around the ruins to the view of the inlet, the view that made this such a strategic location. Feral horses graze on the lawn and drink rainwater from what had once been ornate fountains.

Further on we wander past remains of pool houses, stables, a dairy, then out toward the ocean beyond. The trail, a former road, runs through a maritime forest behind the dunes. Or did. In places the dunes have reclaimed the road as their own. Sand is deep and soft, and hot. After another mile of this we finally debouch onto the beach.

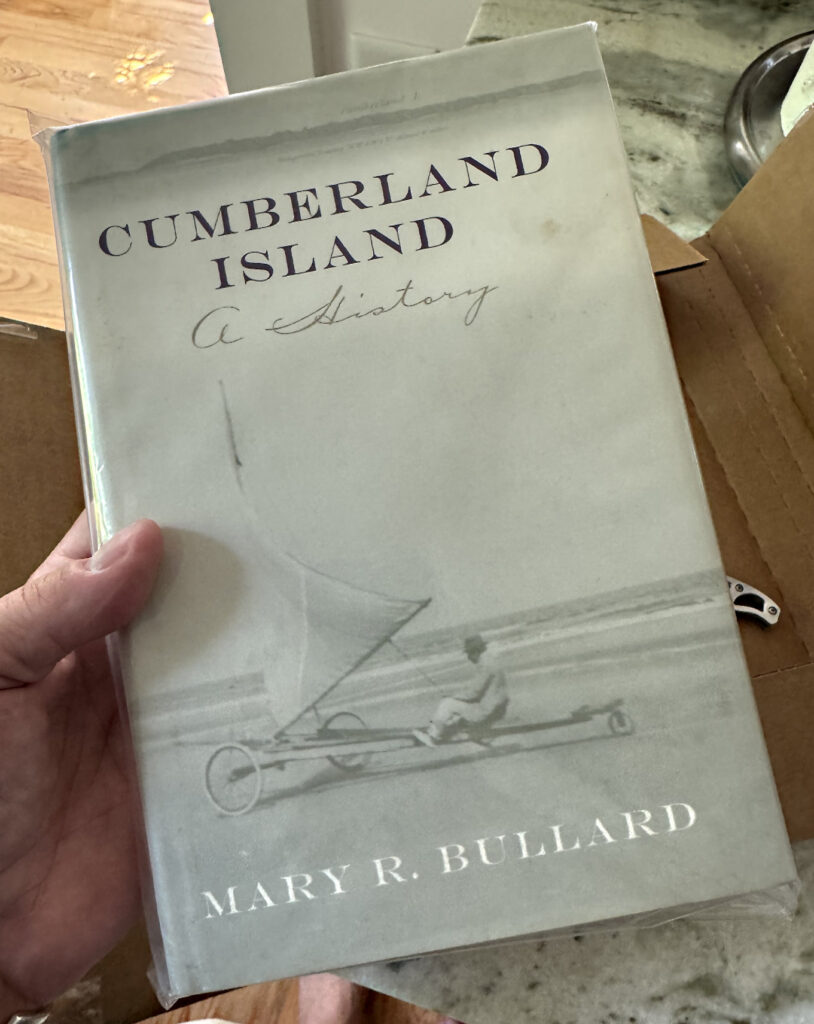

These southern beaches are remarkably wide and flat and hard. In the 1800s, it was popular sport to build sand boats and sail them at high speed for miles. This uncredited photo appears on the cover of “Cumberland Island: A History” authored by one of the Carnegie descendants.

The Florida State Archives has many similar photos taken at Ormond Beach. Honestly, it looks like fun.

Far to the south we can just make out the mouth of the inlet. Rock jetties extend from the shore on each side nearly 3 miles out to sea, for the sea floor is just as flat as the beach. The jetties, with dredging, keep a channel open for passage of submarines, but the rocks are covered at high tide and lie in wait like alligators, ready to chomp an unwary wayfarer. Good example of an aid to navigation becoming a hazard to it.

Another example: Just up the beach we find one of the dredge buoys, its base buried in the sand. Probably broke loose in a storm. These things can weigh six tons. Wouldn’t want to meet one bobbing around in the middle of a dark night on a fiberglass pleasure boat – you’d crumple like soggy origami.

Here on the beach we find ourselves standing at a geographic oxymoron. This very spot on the eastern shore of the US is actually the westernmost point of the entire Atlantic Coast. We are in fact 600 miles west of the easternmost point, up in Maine. If you want to sleep late and still watch the sunrise over the Atlantic, this is the place to do it. When the sun comes up in Maine, you still have over an hour to wait before it rises here. The dredge buoy seems to mark the spot, like the famous bollard in Key West marking the southernmost point in the US.

As owners came and went, livestock was allowed to wander, or simply abandoned. Cattle, hogs, pheasants, goats, and a veritable zoo of exotic creatures remained behind and roamed free for centuries. Today a large herd of wild horses has free rein of the island. Up in the dunes we find a glossy stallion grazing on beach grass.

Another mile up the beach we reach the campground and find a handful of people, the first of the day. We take a dip in the ocean, take cold showers, and head back across the island. The forest canopy is like a big green tent, open underneath.

Striking the river on the west side, we head south on a trail along the shore. Nothing but birds and cabbage palm and Live Oaks draped with Spanish Moss. Finally back at the dock after a four mile round trip, we row back over to Tidings.

There we see a most unexpected sight: a nuclear submarine escorted by a retinue of attendant boats bristling with firepower.

This, we surmise, was the purpose of the “live fire drill” – a ruse, perhaps, to clear the inlet without giving too much away, as it heads to Kings Bay Sub Base across the river. It’s an Ohio Class sub, armed with nuclear Trident ICBM missiles. Each missile costs $70 million, and each sub carries 24 of them. The sub alone costs $3.5 billion. That’s a lot of money and firepower parading by as we relax on the deck of our humble little craft, powered by a one cylinder engine, dining on our one-pot dinner.

It feels like another anachronism, a legacy of the Cold War with its peak nuclear annihilation scare, back when neighbors built bomb shelters in the back yard. “Mutually Assured Destruction” it was called, or just plain MAD, if you were a peacenik. I remember doing Duck and Cover Drills in grade school, as if covering your head with a notebook would save you. An early form of Security Theater.

And here they are, still cruising the oceans half a century later, close enough for me to arouse suspicion in the twitchy escort boats. But the former panic has grown old and tired. We got used to it. We have new scary things to worry about now, though the old scary things never went away. Funny how that works.

Late that night, I wake to the sound of a low rumble and lights flashing in the porthole. Something big is moving upriver sweeping the sound with a blinding spotlight. Or some ship of the future brandishing a laser weapon.

From Spanish Galleons, to pirate frigates, Union gunboats, steam yachts of war-wealthy industrialists, to nuclear subs, there’s a pleasing continuity to it.