Funny how things circle back.

It was the mid-1930’s, at the business end of the last Great Depression, that a young, not quite gainfully employed naval architect named Howard Chapelle signed up for a job with the WPA. Everyone needed work, and the government was creating jobs and funding them as fast as anybody could think of them. Someone in FDR’s administration came up with an idea to put the nations destitute naval architects to work. It was to be called the “Historic American Merchant Marine Survey/” Along with a lot of other projects that came out of the WPA, it would turn out to be an incredibly valuable storehouse of historic documents; though, with humble beginnings and a short life, it’s eventual cultural value would not be evident for quite some time. Of the two largest work programs created by FDR – the CCC and the WPA – it was this one, the WPA, that received harsh criticism as wasteful and unnecessary, particularly from the conservative opposition.

The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) came first, created in 1933, and quickly put over a quarter million unemployed Americans to work planting trees, building parks and roads and bridges and infrastructure. Many, many of these projects were so well designed and constructed they are still in use today. Along the mountain ridge you can see from our house, for example, is the Blue Ridge Parkway and Shenandoah National Park, both of which came out of the CCC. Just up the road from us is “Triple C Camp” – now a camp for kids (where my daughters spent summers). It was originally a CCC worker’s camp built in the 30’s.

Photographers like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans documented the upheaval of rural society with iconic images of the Dust Bow.

The CCC was popular, and successful, but it wasn’t enough. It provided mostly pick-and-shovel type work, enlisting as many bodies in manual labor as possible, and as a result it employed mostly young men with little training or skill. But by the mid-30’s, millions of skilled laborers were also out of work, and women too, so in 1935 Roosevelt started a second program to take up the slack, the WPA. The goal of the Work Projects Administration was not only to create jobs for many of the nations skilled white collar workers, but also for people with no skills who were ill-suited to hard labor or living in the rough conditions of remote work camps. It was this rather broad agenda that left it open to easy criticism, and was the frequent butt of jokes, since of necessity it often paid people a salary for doing what appeared to be very little.

But this criticism overlooked the intrinsic, if less obvious material value of the more creative “make work” projects. In a few cases the value was immediately apparent, but for others it would not be realized for many decades, though even that value was not the primary purpose. The most pressing need was to provide employment for trained professionals on projects in some way connected to their particular field. Otherwise, the country risked losing the valuable skills and training of a whole generation. Photographers and artists, like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, through programs at the FSA, documented the upheaval of rural society with what have become iconic images of the Dust Bowl era. Ethnographers recorded oral histories (I once worked for a man who tramped through Appalachia with a notebook and a Graflex). Writers, teachers, musicians and other people with talent or training were put to work in just about any way imagined.

The “Historic American Merchant Marine Survey” lasted just over a year, but the Smithsonian has difficulty keeping up with demand for the materials.

The “Historic American Merchant Marine Survey” was one such project. It was actually a relatively small program, lasting just over a year before it was cancelled under pressure from FDR’s opponents, but the legacy of that single year of work has proven so valuable the Smithsonian has had difficulty keeping up with demand for copies of the materials it generated. The goal of the project was to survey American working sail craft – to measure, document, and make drawings of hulls and sail plans, along with construction details.

The survey came at a particularly fortunate time. The 1930’s were a transition at end of the age of sail to the modern oil powered era, when affordable gasoline engines replaced not just canvas, but allowed tractors to replace draft horses, and cars to supplant carriages. Not only would World War II change forever the types of vessels used for war and commerce and even pleasure, but many of the men who had the knowledge and skills to construct these traditional American craft would not return from the war, and their knowledge and skills died with them. Many of the boats surveyed by Chapelle and his companions were the last known examples of their kind, found rotting slowly in marshes and abandoned in once working harbors.

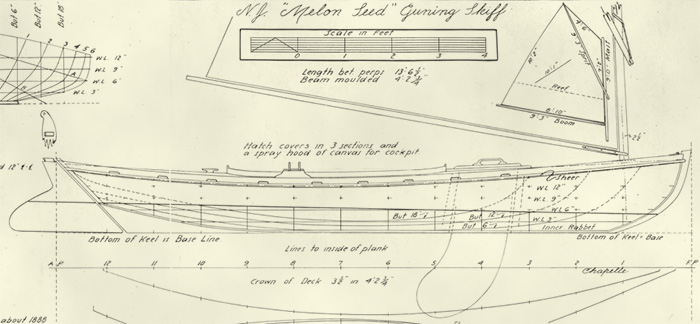

The plans for the “Melon Seed” come from that WPA survey project. It was a small wooden sailing skiff of the 1880’s, designed to be used by one man, primarily for duck hunting in winter in the shallow marshes and choppy bays inside the barrier islands of the Jersey Shore. Variations were used for similar conditions in Delaware, Maryland and Virginia. During the winter, when the fields lay dormant, a farmer could supplement his income and spartan table with wild ducks and geese, if he could get to them. A partial deck on the boat gave protection from the elements, and a rail along the edge kept wet feet and decoys from slipping off, providing a place to tie the ducks. The boat had to be small enough to maneuver in and out of the marshes, with shallow draft, had to be easy drop sail and row, but stable enough to take him safely home across icy and often rough waters of the open bays.

I ordered a set of plans from the Smithsonian for $15 (see below). It’s just one sheet of paper, but contains all that is needed to reconstruct one in traditional materials. With only a few modifications to the plans, newer building methods developed in recent years, using less wood and modern adhesives, can be employed to build the same boats, only lighter and more durable.

So, as I write this 75 years later, the stock market has again lost more than half its value, just since September. Banks are failing or getting bailed out, the auto industry is asking for help to avoid bankruptcy, and the world’s financial markets are teetering on the verge of collapse, the real estate market is a bust, and over half a million Americans lost their jobs last month alone. The price of oil has swung from an all time high to a new low in only a few months, weaving and staggering like a drunk before he keels over.

President elect Obama has promised to combat the New Depression with a new New Deal. I wonder what projects we’ll undertake in the next few years that people will look back on 75 years from now. Will gasoline engines disappear? Oddly enough, sails are starting to appear once again on ocean going ships, in the form of high tech kites. Windmills are going up again. Should we start taking measurements on things like riding mowers and the family van? Will anyone ever again, at some point in the distant future, want to build a sparkly fiberglass ski boat with a v-8 engine, or a bass “fishing” boat with dual 150 horse power Mercury engines, or a tandem jet ski?

History is a strange thing.

– : | : –

You can order plans for the Melonseed, as well as other traditional American Craft from the Historic American Merchant Marine Survey, directly from the Smithsonian. As of this writing, the price has gone up to $20, but now they have an email address for questions – just three years ago, all communication was via US Postal Service. The link to the Smithsonian Ship plans page is:

http://americanhistory.si.edu/csr/shipplan.htm

You’ll still have to mail a check, but ask for plans for the “Melon Seed” New Jersey Gunning Skiff.

melonseed skiff, mellonseed skiff, melon seed, mellon seed

I’m in the process of slowly gathering tools and knowledge to build a wooden boat and though I was planning to build Atkin’s Cabin Boy, the siren call of the Melonseed is hard to resist.

Regardless of the boat I end up building I wanted to let you know this post was very inspirational and well written. I appreciated the interlude in a sea of how-to’s and practical advice one usually finds on boatbuilding blogs. Gives your little boats a soul and some historical context.

Thanks, Victor. It was fun to write. I’m always intrigued by the unexpected connections between things, especially those that seem to have no connection at all.

https://honest-food.net/canvasback-king-of-ducks/

I shared a link to another blog I follow. I thought you would find this interesting as I know you are interested in history, especially around the time your melonseed plans were first drawn. The Waldorf Hotel in New York City only had one kind of duck on its menu then, Canvasback! These were likely sourced by market hunters, perhaps even melonseed and other, “gunning skiff”, sailors, hunting on Barnagat Bay. I’ve made the dish with other species, (haven’t been lucky enough to source a canvasback), along with Waldorf Salad. Give it a try sometime. It’ll remind you what those boats were really designed for!

Thanks! Certain types of ducks were especially favored for their flavor, and were hardest hit by hunting pressure. The Canvasback was definitely one of those. Here on the Chesapeake, during the winter season hunters sailed from the gunning grounds across the Bay to sell directly to restaurants in Baltimore. Even today, with all the conservation measures, those species are rare.